Neurofeedback for Optimal Performance

Human performance as a construct can be understood as a wide range of human capacity and associated self-directed purposeful physical and mental function. Graphic ©PRESSLAB/Shutterstock.com.

.jpg)

At one extreme is a person living with limited capacity and significant dysfunction (slow car). At the other extreme is a master athlete with enhanced capacity due to genetics and training (fast car).

There is little doubt that mitigating cellular damage by reducing toxins and enhancing cell function with nutrients, rest, and performance training leads to greater capacity and greater performance output. Age-related health and performance decline is also a known variable for which optimal brain and body performance training at any age is desired by professional athletes, corporate executives, and consumers alike. We won't address this method of optimizing peak performance; rather, we will address electrophysiology measures and manipulation to enhance performance.

One other attribute is the mechanisms underlying optimal performance over time or longevity. All human systems face age-related decline, including athleticism (Ganse et al., 2018). Military athletes exposed to unique and deleterious routines (i.e., sleeplessness, night shifts, high tempo engagements that maintain sympathetic arousal) can experience faster rates of decline as a result of mission-essential over-training and a more kinetic type of physical damage (i.e., parachute landings, very heavyweight loads on the musculoskeletal system and exposure to training or during deployment mission injury).

Unlike professional impact sports (i.e., MMA, football), military SOF athletes have far more exposure to high central nervous system stressors within a given month than a typical professional athlete. Also, more unique to military athletes are the critically essential maintenance of cognitive functions to use complex electronics and other equipment under high stress and fatigue conditions while maintaining a heightened situational awareness of potential threats.

BCIA Blueprint Coverage

This unit addresses V. Neurofeedback Optimal Performance Protocols. This unit covers Performance Attributes in qEEG, Culture and Goals of Neurofeedback in Performance, Evolution of Neurofeedback Protocols for Optimal Performance, Introduction to Alpha-Theta Training, Introduction to SMR Training, qEEG-Based NFB Implementation, Remote & Home-Use Performance Training, Monitoring Training, Measuring Progress, and Generalization to Field/Duty Performance, and Full Neurofeedback Session Demonstrations.

A. PERFORMANCE ATTRIBUTES IN qEEG

This section covers Performance Attributes in qEEG, including:

1) Focus and Attention,

2) Stress and Anxiety, and

3) Mood and Attitude.

Overview

Physical strength and flexibility remain essential attributes of optimal performance athletes, civilian or military. Graduated improvements in these areas are well understood and include proper rest, cell recovery, and nutritional support.When it comes to training using biofeedback and neurofeedback, optimal performance for civilian athletes and military athletes looks somewhat different than how it is applied to a clinical population.

Wilson and Peper (2011) observed that while patients seek biofeedback to reduce adverse symptoms, athletes seek the technology to optimize performance. They also recognized that there are baseline differences between athletes and non-athletes.

Athletes often differ from typical patients. Male and female athletes resemble each other more than they resemble the sex norms of the average population on a wide variety of measures. They are motorically, psychologically, and anatomically different as their underlying brain mechanisms and structures are different. At this time, it is unknown whether these differences are due to genetics, early learning, or extensive practice. Most likely they are the result of an ongoing interaction of these three variables. (Wilson & Peper, 2011).

Focus and Attention

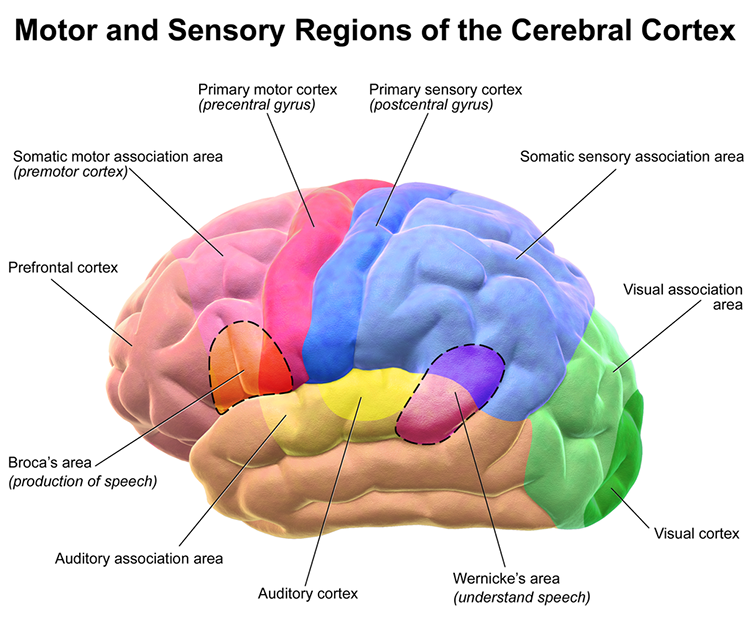

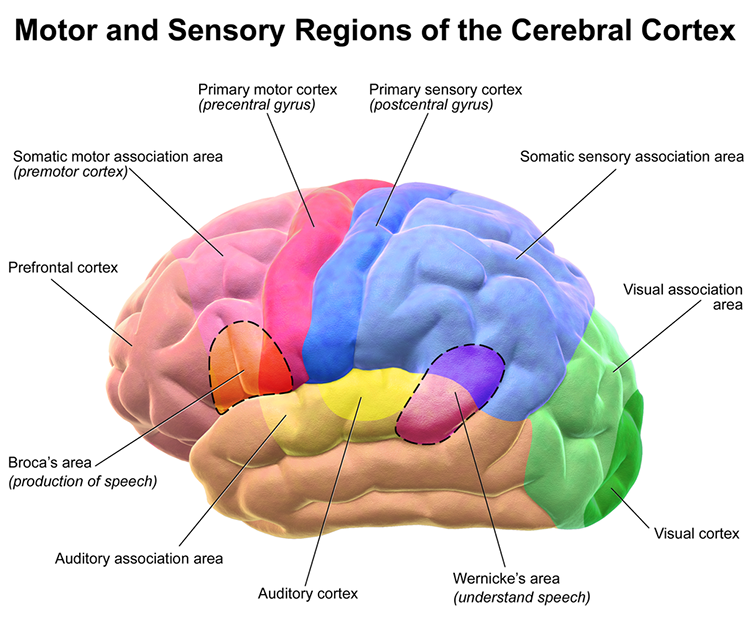

One of the more important cognitive skills essential for military athletic performance is the capacity to engage and maintain focus and attention to detail when it matters.The first step is to properly measure the baseline or current brain state related to focus and attention capacity. Focus and attention to “what” matters too. Part of attention to detail involves the sensory processing functional capacity. The brain’s sensory system involves input from both external (extra-receptors) and internal to the body (intra-receptors) stimuli (e.g., pain, heat, touch, smell, sound).

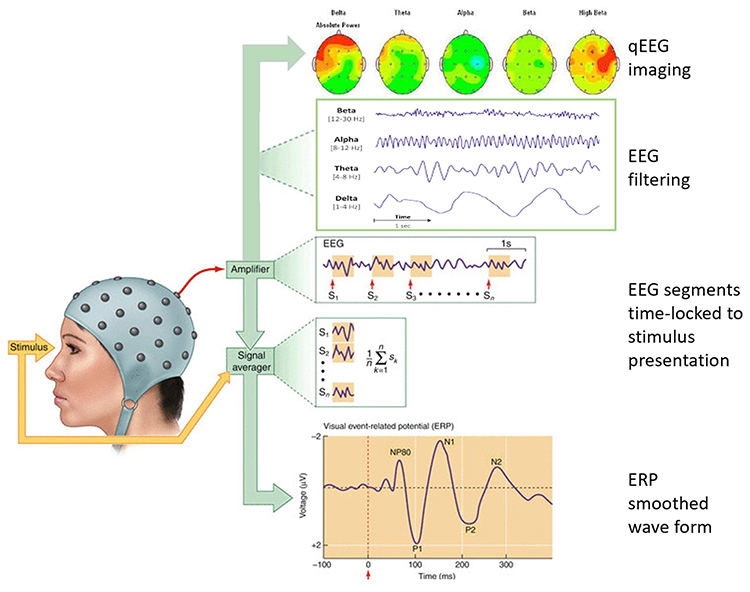

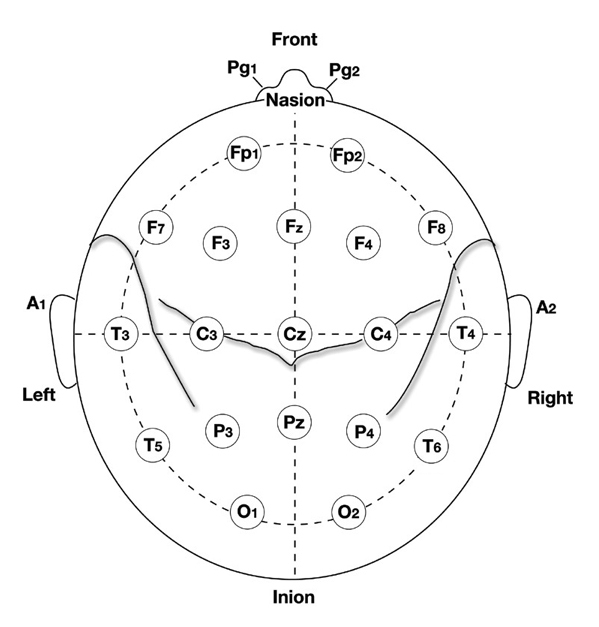

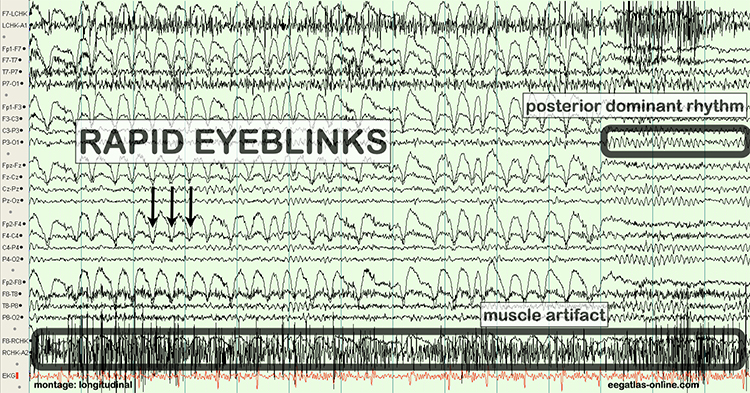

EEG recordings are perhaps the best and least invasive way to reliably evaluate the brain's capacity to orient or attend to stimuli.

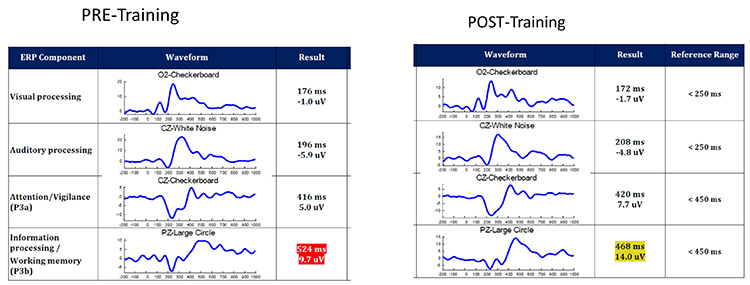

Two primary methods are event-related potentials and EEG/qEEG measurement of frequency values. First, we can measure event-related potentials (ERPs) specific to the function and region of cortical involvement in that function.

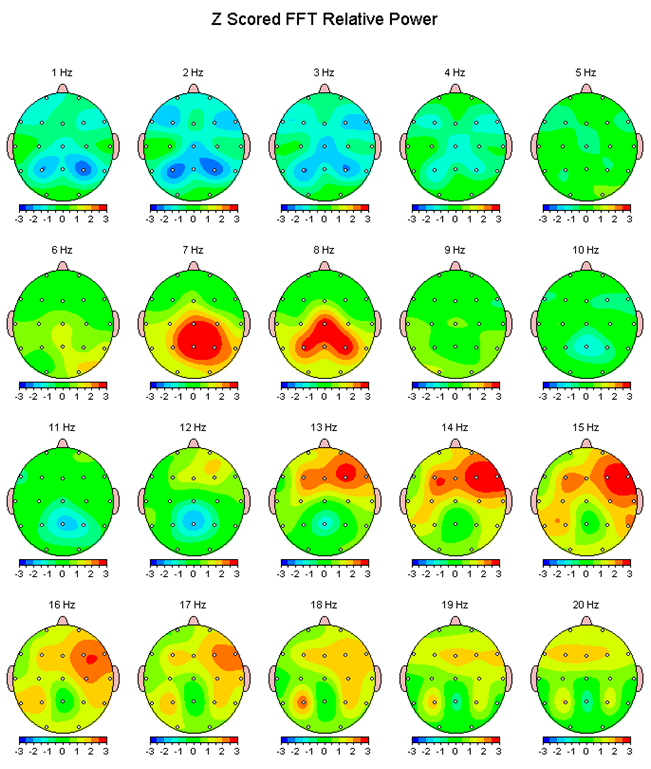

Second, we can measure EEG/qEEG frequency values at cortical regions of interest and calculate those values against a reference group.

Event-Related Potentials: Basic Principles

When a person is exposed to a stimulus (e.g., a flash of light or a movement off to the side of the visual field or an atypical sound), the brain does something called desynchronization. This can be seen by a fast and brief suppression of EEG frequencies in the alpha and beta bands. It appears that these EEG frequencies are involved in the processing or modulation of information flow along neural networks.It is common to record sensory processing speed using ERPs, where a sensory stimulus is presented, and the change post-stimulus delivery can be quantified from the recording EEG. More complex mental processes, or higher-order cognition, are also measured with ERP. For peak performance applications, the value of rapid sensory responses and, likewise, rapid cognitive processing of information can measure baseline function and improvements with training (e.g., react to contact drills).

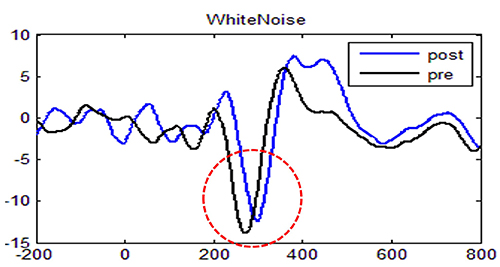

Event-Related Potentials: Sensory N100

In this example of auditory processing to a white noise sound (recorded at CZ), you will see a baseline measure (black line) followed by a post measure (blue line) after induced fatigue. The deep fatigue resulted in a reduced amplitude and delayed or longer latency. While we call this component N100, you will note that the waveform is closer to N200.

The complexity of the stimulus used to produce the component matters. You cannot compare a high-frequency beep tone to a longer-duration white noise sound. Each produces different ERP components.

The difference may be trivial for clinical applications, but for athletic performance or reaction to contact scenarios, 50 milliseconds makes a difference.

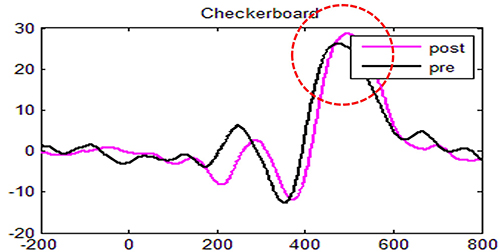

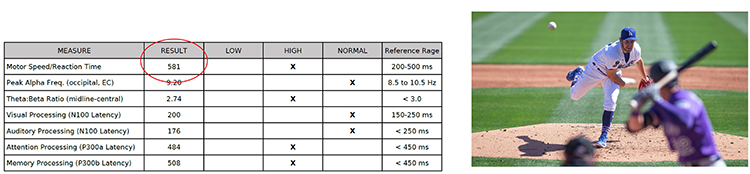

In this example of visual attention to one's external surroundings (black and white checkerboard stimulus, sensor recording at CZ), you will see a baseline measure (black line) followed by a post measure (pink line) after induced fatigue. The deep fatigue resulted in a negligible amplitude and latency difference. While we call this component P300a, you will note that the positive amplitude peak is closer to 500ms. Different tasks or stimulus presentation types will result in differing average latency and amplitude. Normal latency is also age- and gender-sensitive. This is why stimulus types are consistently used when comparing performance improvements.

The P300a component is dopamine-mediated and reflects frontal working functions that are not only associated with attention and focus but also indirectly involved in memory. If a person cannot attend to external environmental stimuli, it is less likely that the information will be available for further processing of that data into memory.

In the context of mind-body integration, Harvard Medical School sports psychiatrist Eric Leskowitz, MD (2017) wrote, “Consider an application: the observed 37 msec decrease in reaction time would enable a baseball player to perceive a 90 mph fastball as though it was only traveling 80 mph. A key feature of the flow state is the sense of time slowing down or stopping” (p. 1).

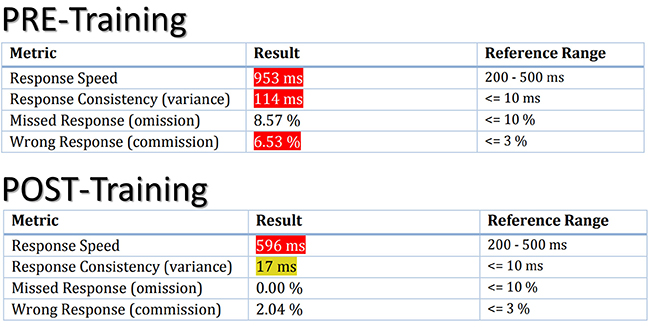

ERPs and continuous performance task measures provide objective millisecond measures to evaluate and monitor peak performance (Mirifar et al., 2019). The number of training sessions is as important as the type of training (protocol) for neurofeedback (Domingos et al., 2021). Less than a dozen trials, especially if mixed with differing protocols, are less likely to yield large enough cortical changes where “the difference, really makes a difference.”

Case Example

Graphic © Mike Orlov/Shutterstock.com

GOAL: In a case study of a professional boxer, nutritionists and sports psychologists incorporated neurofeedback to help the athlete gain focus and improve impulse control (Larson et al., 2012).METHOD: The athlete completed 25 neurofeedback sessions designed to suppress slower frequency EEG power while increasing beta1 frequencies in the frontal and bilateral temporal locations. An additional 17 sessions were completed to inhibit the power of the faster EEG frequencies and augment slow-mid spectrum frequencies recorded from the parietal scalp locations.

RESULT: The result or target of success from the intervention was that the boxer was able to experience a sense of heightened focus yet with a calmness of mind.

Stress and Anxiety

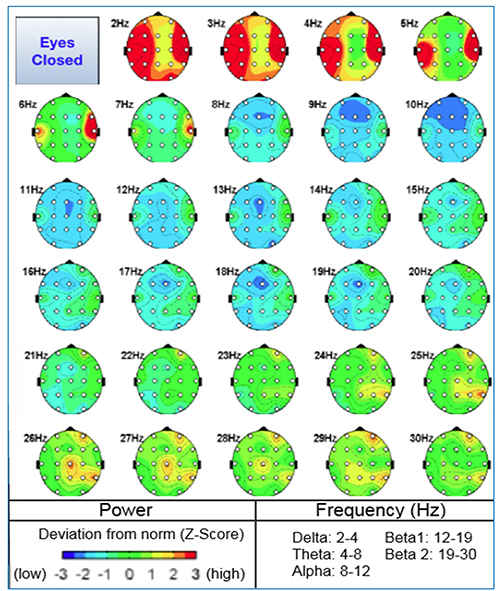

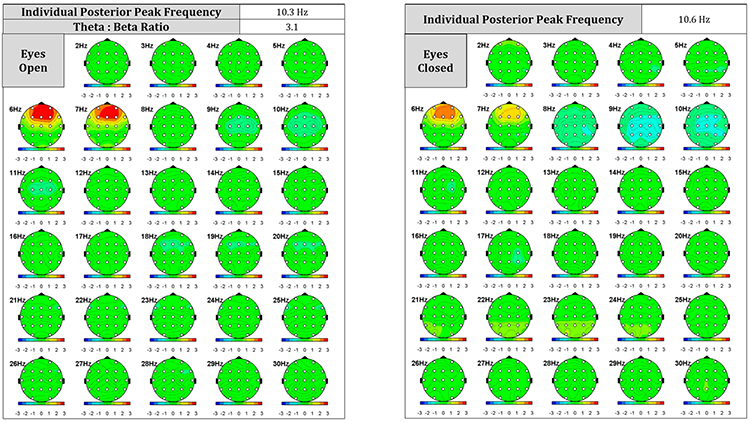

Cognitive or mental strength and flexibility are also becoming better understood and differentiate between amateur athletes and those who excel at the professional level.In a 2014 study of amateur and professional athletes, qEEG results identified that posterior and occipital region alpha frequency band power was lower than typical when experiencing performance anxiety, both for armature and professional athletes (Tharawadeepimuk & Wongsawat, 2014).

However, when it was time for fully-engaged competition, only the professional athlete showed a return to normal alpha power.

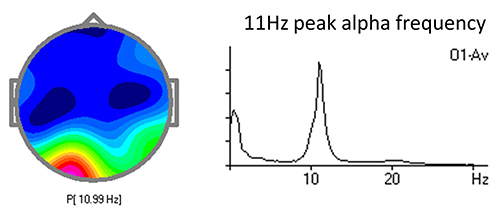

Motor and cognitive performance have been linked with EEG frequencies in the alpha band, making it a reasonable neurofeedback target to optimize performance (Mottaz et al., 2015).

With as little as seven sessions of alpha coherence neurofeedback applied over healthy subjects' motor cortex, the results were lasting and improved hand motor performance (Mottaz et al., 2015).

Beyond motor reaction time and calmness under stressful conditions, the ability of the central nervous system to remain capable of continued learning and detailed recall, alpha peak training has also been reported to aid memory functions.

Memory is not simply a critical cognitive function for older adults and laypeople. Military athletes need to perform well in advancing and complex use of battlefield equipment. The additional use of memory enhancement, even related to language learning, is an important and underrecognized optimal performance target for neurofeedback (Nan et al., 2012)..

The thalamic generation of alpha has been implicated in anxiety. Theta/alpha ratio neurofeedback effectively modulates this important stress-response function (Zadkhish et al., 2017).

In a study of male soccer players, 12 alpha/theta neurofeedback sessions at scalp location PZ were provided. Compared to the control group, the neurofeedback group demonstrated reduced performance anxiety and enhanced athletic performance (Tharawadeepimuk & Wongsawat, 2016).

The Kim’s Game (keep-in-memory-system) has been around over 100 years and is utilized among military trainers to enhance situational awareness and several memory functions. It is applied under stress conditions and without, all to aid in the improved cognitive processing and memory of those that need recall accuracy following brief observation periods. Training memory skills under stress is done to train the brain to process only the relevant sensory information and suppress irrelevant information.

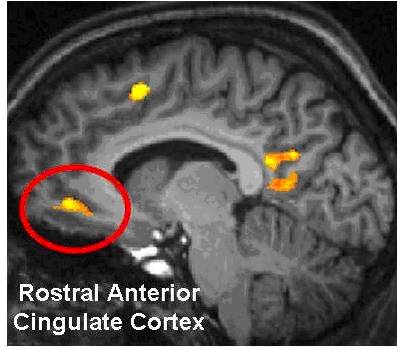

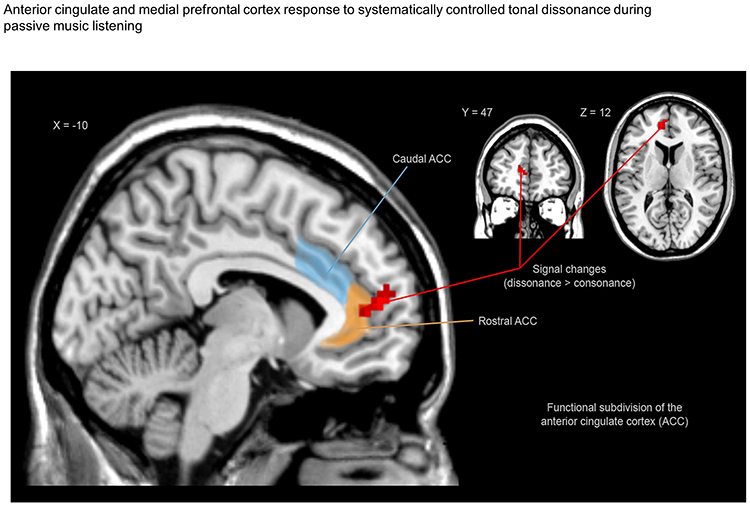

One frequently targeted brain region related to the application of attention to detail while under stress is the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC). The anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) if often a target of neurofeedback training for several reasons. The ACC is heavily involved in the ability to monitor actions and the results of actions from which adjustments could be made. The ACC is therefore involved in decision making, a critical skill on the fast-moving sports arena or the battlefield.

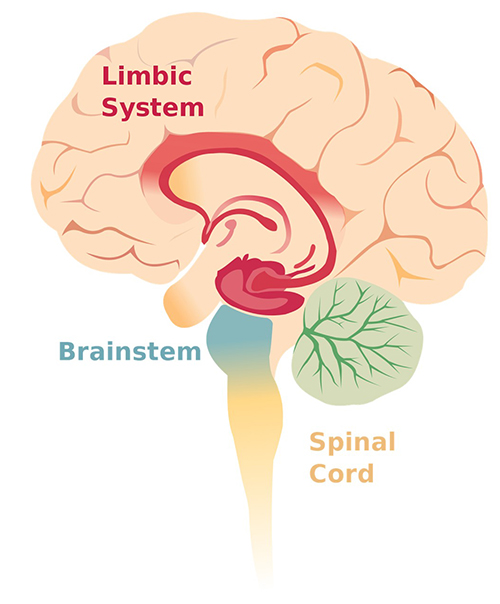

The ACC has structural divisions that are loosely referred to as “parts” and collectively serve our function of monitoring the environment. These are the motor input with connections to all motor areas in the brain, the affective input (called the limbic part) influenced by the amygdala and thalamus. The affective input (called the limbic part) is influenced by the amygdala and thalamus. Most dorsally in the ACC is the cognitive part.

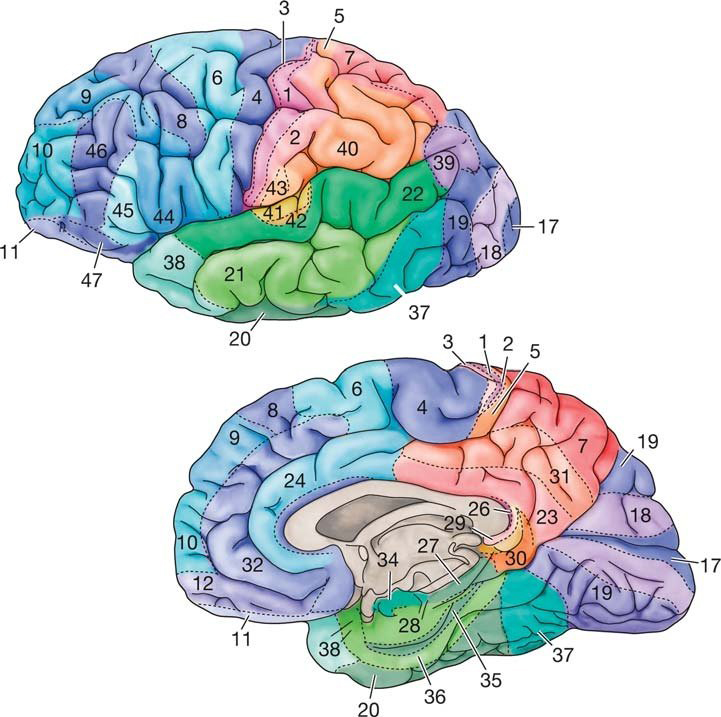

According to the theory proposed by Bush and collaborators (Bush et al., 2000), the ACC presents a functional division in which caudal‐dorsal regions (blue color) serve a variety of cognitive functions, whereas rostral‐ventral regions are involved in emotional tasks (orange color). The red color indicates fMRI results, sagittal view showing stronger signals during dissonance (compared to consonance) in the left medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) and the left anterior cingulate cortex (ACC).

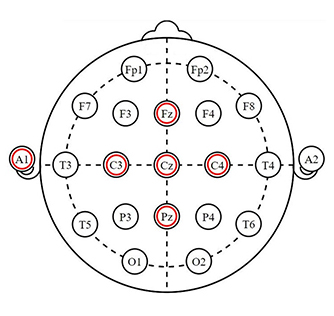

Neurofeedback applications have been specifically developed for athletes by capitalizing on this important and multi-function ACC brain region, and may well represent the more commonly modulated region of the brain among neurofeedback providers and consumer-facing protocols. Single sensor/electrode training over CZ or FZ has alone been shown to be very effective in the training of attention, focus, and anxiety.

|

|

By suppressing elevated beta2 frequency power, one may see reduced anxiety expression. Commonly, this is trained in conjunction with heart rate variability biofeedback.

With the reduction of slow content (theta) dominance in the EEG over the ACC, one may see improved focus and attention.

With ACC function training, event-related potentials are often used to record the orienting response, a function of awareness. Specifically, the P300a and P400, that occur under the “NoGo” stimulus condition, serve to show the number of milliseconds the brain takes to process this monitoring function.

Mood and Attitude

Affect, another word for “mood,” is also connected to the ACC as was discussed within the context of limbic system input.

Mood is a conscious awareness of one's affective or emotional state. It adds a dimension to our reasoning and decision-making and, when imbalanced, will also reduce functions of attention or focus. Basic emotions include anger, fear, joy, sadness, disgust, ands surprise. More complex are conditions of sympathy, guilt, admiration, and contempt. Most everyone’s brain is wired to seek positive emotions and avoid difficult emotions. In some instances, this sets up a motivating condition where behaviors like excessive alcohol consumption temporarily modulate emotions in a more desirable direction.

In general, the limbic lobe, in synchrony with the hypothalamus and amygdala, has been described as serving the role of mood or emotional states. This is not to say that mood and emotion are limited to these structures. Rather, the system that produces affect involves cortical and non-cortical interconnections that are responsive to internal and external stimuli.

Moods and attitudes that are challenging carry terms like depression, sadness, worry, and anxiety. Moods and attitudes that are positive carry terms like joy, contentment, and happiness.

Both mood and attitude states are in part regulated by the brain’s monitoring capacity, with the ACC being a contributing structure that is readily accessed for modulation with neurofeedback, the from anterior regions in particular (F3, FZ, F4).

For many years, the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) was determined to be a more dominant location of the frontal lobes related to mood. Specifically, if there was hypofunction in the left frontal region of interest, depressed or flat mood was a likely correlation. Some researchers in the 1990s found a correlation between depression and frontal alpha asymmetry (FAA), which is where the left frontal (F3) alpha activity was greater than that on the right (F4).

There does seem to be a relationship with hypofunction among the left DLPFC. Still, research by Dr. Martijn Arns has convincingly demonstrated that an alpha asymmetry score is diagnostically insufficient as a single ratio value (van der Vinne et al., 2017). Of note, the FDA approved rTMS 10Hz neurostimulation to the left DLPFC for Major Depressive Disorder and Bipolar Disorder based on strong clinical evidence. As seen by mixed results of left DLPFC 10Hz rTMS, the different subtypes of depressed mood are evidenced by different EEG patterns beyond just FAA.

Regarding peak performance, improved mood is correlated with improved focus, sleep recovery, and overall optimized function. Neurofeedback has been applied successfully using different frequency and scalp placement protocols (Lee et al., 2019; Linden, 2014).

Subjective explanations from those that train the brain with NFK report improved control over thought processes and mood regulation. It is this more subjective expression, seen in behavior and carried over to motivation to excel, that we find “attitude” to be relevant for optimal performance. Because affect is so tightly related to attitude, it is often a target of neurofeedback.

Mindfulness is a key pathway towards improved mood and attitude. Those who practice mindfulness meditation report feeling more “clear-headed” and able to perform without hindering self-judgment (Birrer et al., 2012; Tingaz & Çakmak, 2021).

The main asymmetry-based EEG-NF protocol has used an asymmetry index of alpha power as a feedback signal and trained patients to increase the right-to-left ratio, essentially rebalancing a putative hypoactivation of the left hemisphere. This asymmetry index is computed as A=100x(R-L)/R+L), where R and L are the square root of the power of alpha activity (obtained by Fast Fourier Transformation) measured at a right and left frontal electrode, respectively.

Meditation training has been found to influence alpha and theta frequency bands and modulate the Default Mode Network, a brain network instrumental in quality sleep and anxiety management (Nicholson et al., 2020). In particular, slower alpha (alpha1), theta modulation, and reduced beta frequency power are reported with hypnosis and meditation.

Occipital alpha power increases with meditation training and alpha training to increase and decrease power using MRI-neurofeedback has been used (personal communication with Dr. Ruth Lanius) to reduce symptoms of PTSD. The influence of alpha neurofeedback and meditation on the DMN is experiences in what appears to be a strengthening of one’s “self-referential” thoughts and attitude. This is the brain’s process of taking in external stimuli from around you and seeing yourself in that context. It is a more self-reflective capacity that can temper attitude and mood.

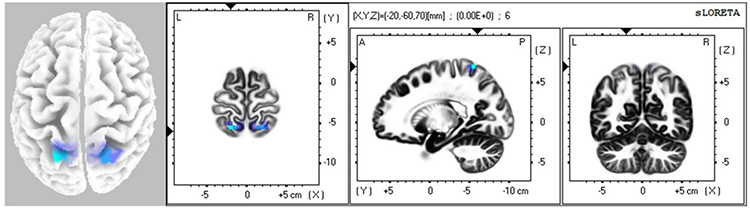

LORETA has been used to define brain regions of interest related to both neurofeedback and meditation. The use of LORETA with meditation reflects that beta is reduced within the ACC, and theta/alpha is enhanced in the posterior cingulate cortex (PCC), cuneus and precuneus. The use of neurofeedback at central midline locations (Fz, Cz, Pz) permits these frequencies and locations within the DMN to likewise be modulated. The result is potential mood stability through greater self-regulation capacity (Braboszcz & Delorme, 2011; Braboszcz et al., 2010; Brandmeyer & Delorme, 2013; Cahn et al., 2013; DeLosAngeles et al., 2016; Deolindo et al., 2020; Fingelkurts et al., 2016; Josipovic, 2010; Lazar et al., 2005; Lomas et al., 2015; Lutz et al., 2004; Travis & Parim, 2017; Zhigalov et al., 2019).

Alpha and theta neurofeedback share many similarities with mindfulness meditation with the advantage of objective EEG measures with neurofeedback. Both modalities facilitate improved concentration and emotional regulation.

Emotional regulation is considered a frontal lobe function and behaviorally can also be characterized as a facet of attitude. Learning to gain cognitive control with either neurofeedback or meditation has direct peak performance benefits.

References

Birrer, D., Röthlin, P., & Morgan, G. (2012). Mindfulness to enhance athletic performance: Theoretical considerations and possible impact mechanisms. Mindfulness, 3(3), 235–246. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-012-0109-2

Braboszcz, C., & Delorme, A. (2011). Lost in thoughts: Neural markers of low alertness during mind wandering. NeuroImage, 54(4), 3040–3047. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.10.008

Braboszcz, C., Hahusseau, S., & Delorme, A. (2010). Meditation and neuroscience: From basic research to clinical practice. In R. Carlstedt (Ed.), Integrative clinical psychology, psychiatry and behavioral medicine: Perspectives, practices and research. Springer Publishing.

Brandmeyer, T., & Delorme, A. (2013). Meditation and neurofeedback. Frontiers in psychology, 4, 688. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00688

Bush, G., Luu, P., & Posner, M. I. (2000). Cognitive and emotional influences in anterior cingulate cortex, Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 4(6), 215-222. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1364-6613(00)01483-2

Cahn, B. R., Delorme, A., & Polich, J. (2013). Event-related delta, theta, alpha and gamma correlates to auditory oddball processing during Vipassana meditation. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 8(1), 100–111. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nss060

DeLosAngeles, D., Williams, G., Burston, J., Fitzgibbon, S. P., Lewis, T. W., Grummett, T. S., Clark, C. R., Pope, K. J., & Willoughby, J. O. (2016). Electroencephalographic correlates of states of concentrative meditation. International Journal of Psychophysiology: Official Journal of the International Organization of Psychophysiology, 110, 27–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2016.09.020

Deolindo, C. S., Ribeiro, M. W., Aratanha, M. A., Afonso, R. F., Irrmischer, M., & Kozasa, E. H. (2020). A critical analysis on characterizing the meditation experience through the electroencephalogram. Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience, 14, 53. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnsys.2020.00053

Domingos, C., & Peralta, M., Prazeres, P., Nan, W., Rosa, A., & Pereira, J. (2021). Session frequency matters in neurofeedback training of athletes. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 46(2), 195-204. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10484-021-09505-3

Fingelkurts, A. A., Fingelkurts, A. A., & Kallio-Tamminen, T. (2016). Long-term meditation training induced changes in the operational synchrony of default mode network modules during a resting state. Cognitive Processing, 17(1), 27–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10339-015-0743-4

Ganse, B., Ganse, U., Dahl, J., & Degens, H. (2018). Linear decrease in athletic performance during the human life span. Frontiers in Physiology, 9, 1100. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2018.01100

Josipovic Z. (2010). Duality and nonduality in meditation research. Consciousness and cognition, 19(4), 1119–1123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2010.03.016

Larson, N. C., Sherlin, L., Talley, C., & Gerais, M. (2012). Integrative approach to high-performance evaluation and training: Illustrative data of a professional boxer. Journal of Neurotherapy, 16(4), 285-292. https://doi.org/10.1080/10874208.2012.729473

Lazar, S. W., Kerr, C. E., Wasserman, R. H., Gray, J. R., Greve, D. N., Treadway, M. T., McGarvey, M., Quinn, B. T., Dusek, J. A., Benson, H., Rauch, S. L., Moore, C. I., & Fischl, B. (2005). Meditation experience is associated with increased cortical thickness. Neuroreport, 16(17), 1893–1897. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.wnr.0000186598.66243.19

Lee, Y. J., Lee, G. W., Seo, W. S., Koo, B. H., Kim, H. G., & Cheon, E. J. (2019). Neurofeedback treatment on depressive symptoms and functional recovery in treatment-resistant patients with major depressive disorder: An open-label pilot study. J Korean Med Sci., 34(42), e287. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2019.34.e287

Leskowitz, E. (2017). The zone: A measurable (and contagious) exemplar of mind–body integration. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 23(5), pp. 324–325. http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/acm.2017.29023.ejl

Linden D. E. J. (2014). Neurofeedback and networks of depression. Dialogues Clin Neurosci., 16(1), 103–112. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2014.16.1/dlinden

Lomas, T., Ivtzan, I., & Fu, C. H. (2015). A systematic review of the neurophysiology of mindfulness on EEG oscillations. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 57, 401–410. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.09.018

Lutz, A., Greischar, L. L., Rawlings, N. B., Ricard, M., & Davidson, R. J. (2004). Long-term meditators self-induce high-amplitude gamma synchrony during mental practice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 101(46), 16369–16373. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0407401101

Mirifar, A., Keil, A., Beckmann, J., & Ehrlenspiel, F. (2019). No effects of neurofeedback of beta band components on reaction time performance. J Cog Enhanc, 3, 251-260. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41465-018-0093-0

Mottaz, A., Solcà, M,, Magnin, C., Corbet, T., Schnider, A., & Guggisberg, A. G. (2015). Neurofeedback training of alpha-band coherence enhances motor performance. Clinical Neurophysiology, 126(9), 1754-1760. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinph.2014.11.023

Nan, W., Rodrigues, J. P., Ma, J., Qu, X., Wan, F., Mak, P. I., Mak, P. U., Vai, M. I., & Rosa, A. (2012). Individual alpha neurofeedback training effect on short term memory. International Journal of Psychophysiology: Official Journal of the International Organization of Psychophysiology, 86(1), 83–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2012.07.182

Nicholson, A. A., Ros, T., Densmore, M., Frewen, P. A., Neufeld, R., Théberge, J., Jetly, R., & Lanius, R. A. (2020). A randomized, controlled trial of alpha-rhythm EEG neurofeedback in posttraumatic stress disorder: A preliminary investigation showing evidence of decreased PTSD symptoms and restored default mode and salience network connectivity using fMRI. NeuroImage: Clinical, 28, 102490. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2020.102490

Tharawadeepimuk, K. & Wongsawat, Y. (2014). QEEG evaluation for anxiety level analysis in athletes. The 7th 2014 Biomedical Engineering International Conference, 1-4. http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/BMEiCON.2014.7017400

Tharawadeepimuk, K. & Wongsawat, Y. (2016). QEEG coherence evaluation for soccer performance level analysis of the striker. In R. Wang R. & X. Pan (Eds.). Advances in cognitive neurodynamics. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-0207-6_51

Tingaz, E.O., & Çakmak, S. (2021). Mindfulness, self-compassion, and athletic performance in student-athletes. J Rat-Emo Cognitive-Behav Ther. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10942-021-00434-y

Travis, F., & Parim, N. (2017). Default mode network activation and Transcendental Meditation practice: Focused Attention or Automatic Self-transcending?. Brain and Cognition, 111, 86–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandc.2016.08.009

van der Vinne, N., Vollebregt, M. A., van Putten, M. J. A. M., & Arns, M. (2017). Frontal alpha asymmetry as a diagnostic marker in depression: Fact or fiction? A meta-analysis. NeuroImage: Clinical, 16, 79-87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2017.07.006

Wilson, V., & Peper, E. (2011). Athletes are different: Factors that differentiate biofeedback/neurofeedback for sport versus clinical practice. Biofeedback, 39(1), 27–30. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-39.1.01

Zadkhosh, S. M., Zandi, H. G., & Hemayattalab, R. (2017). The effects of Neurofeedback on anxiety decrease and athletic performance enhancement. Journal of Applied Psychological Research, 7(4), 21-37. https://doi.org/10.22059/japr.2017.61078

Zhigalov, A., Heinilä, E., Parviainen, T., Parkkonen, L., & Hyvärinen, A. (2019). Decoding attentional states for neurofeedback: Mindfulness vs. wandering thoughts. NeuroImage, 185, 565-574. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.10.014

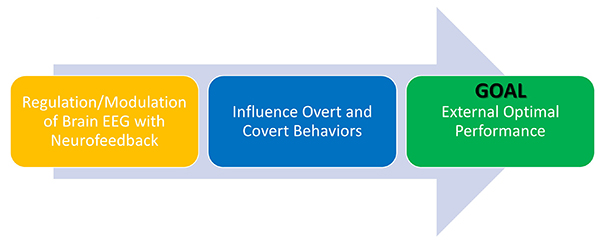

B. CULTURE AND GOALS OF NEUROFEEDBACK IN PERFORMANCE

NFB offers several methods or types, but they are all designed to deliver changes to the brain networks through EEG regulation. Examples include LORETA Brodmann targeting z-score, select frequency range amplitude, frequency, and site selected coherence. Each method is designed to alter behaviors. Examples are covert thoughts and self-reflection, mood stability, motor processing speed, anxiety reduction, memory, and a combined relaxation with increased focus/attention. The end result is a more efficient brain and nervous system equipped to meet performance demands (athletic skills, shooting accuracy, restful sleep) through increased neuroplasticity resulting in a greater capacity to self-regulate one's internal cognitive state.

Frequency and Location for Neurofeedback for Performance (Anmin et al, 2021; Doppelmayr et al., 2008; Xiang et al., 2018).

SMR (C3, CZ, C4) 12-15Hz enhance while inhibiting theta 3-7Hz and beta 18-30Hz

Frontal Alpha reduction (8-12Hz)

Frontal theta reduction

Frontal, Central, Parietal Beta reduction

Alpha/Theta Crossover (PZ, OZ)

References

Doppelmayr, M., Finkenzeller, T., & Sauseng, P. (2008). Frontal midline theta in the pre-shot phase of rifle shooting: differences between experts and novices. Neuropsychologia, 46(5), 1463–1467. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2007.12.026

Gong, A., Gu, F., Nan, W., Qu, Y., Jiang, C., & Fu, Y. (2021). A review of neurofeedback training for improving sport performance from the perspective of user experience. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 15, 638369. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2021.638369

Xiang, M.-Q., Hou, X.-H., Liao, B.-G., Liao, J.-W., & Hu, M. (2018). The effect of neurofeedback training for sport performance in athletes: A meta-analysis. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 36, 114-122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2018.02.004.

C. EVOLUTION OF NEUROFEEDBACK PROTOCOLS FOR OPTIMAL PERFORMANCE

This section covers Early Protocols (Training Protocols, Defining an Effective Training Protocol, and Primary Schools of Thought in Neurofeedback Training) and Selecting a Protocol Model.

Overview

The development of training protocols in neurofeedback has been the result of an evolution of training practices, some growing out of early observational results related to research studies and some developing from attempts to elicit responses in the human or animal EEG that were either atypical or were an attempt to enhance already existing characteristics. This section will explore the history of this evolution and some of the significant milestones that have guided neurofeedback clinical applications during its 60+ year history.

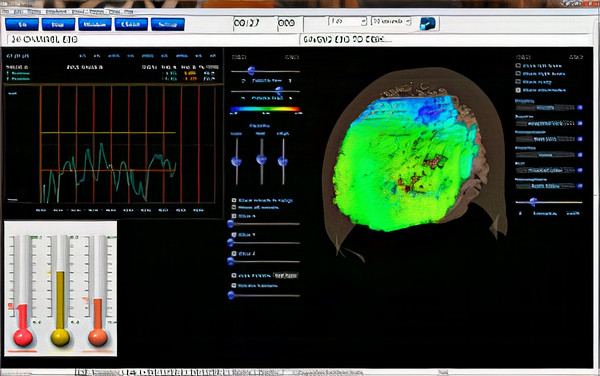

The term protocol refers to a procedure for teaching individuals to achieve proficiency through instruction and practice. This definition works quite well for neurofeedback training and is an excellent description of the process. Neurofeedback training is a training process that utilizes reinforcement and instruction to enable an individual to develop improved proficiency or skill in a particular cognitive, mental or central nervous system activity-related task. Graphic courtesy of BrainMaster.com.

Generally accepted definitions of neurofeedback suggest that it is a process of operant conditioning leading to self-regulation of brain activity. Marzbani and colleagues (2016) state that “Neurofeedback is a kind of biofeedback, which teaches self-control of brain functions to subjects by measuring brain waves and providing a feedback signal.”

However, Strehl (2014) wrote that the learning process associated with neurofeedback requires more than operant conditioning and simple feedback. We also need to understand the influence of classical conditioning, skill learning, and motivational aspects.

She noted that all types of learning, including neurofeedback, result from trial and error, conscious and unconscious responses to events, including feedback and reinforcement, and an awareness of the results of such efforts. To facilitate the ability to incorporate these new skills into everyday life, known as generalization, we need to incorporate a behavioral therapy approach to the process of neurofeedback training. Therefore, our analysis of the development of training protocols will include evaluating which protocols may more effectively meet the client's needs in light of the learning requirements noted above.

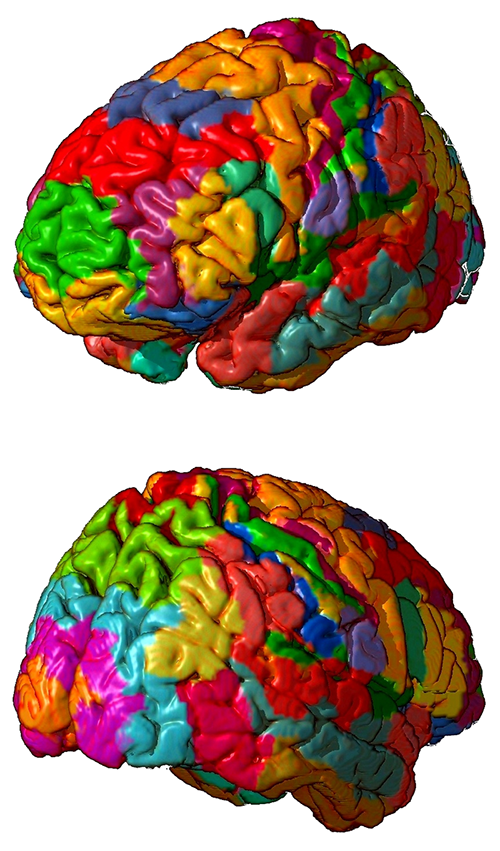

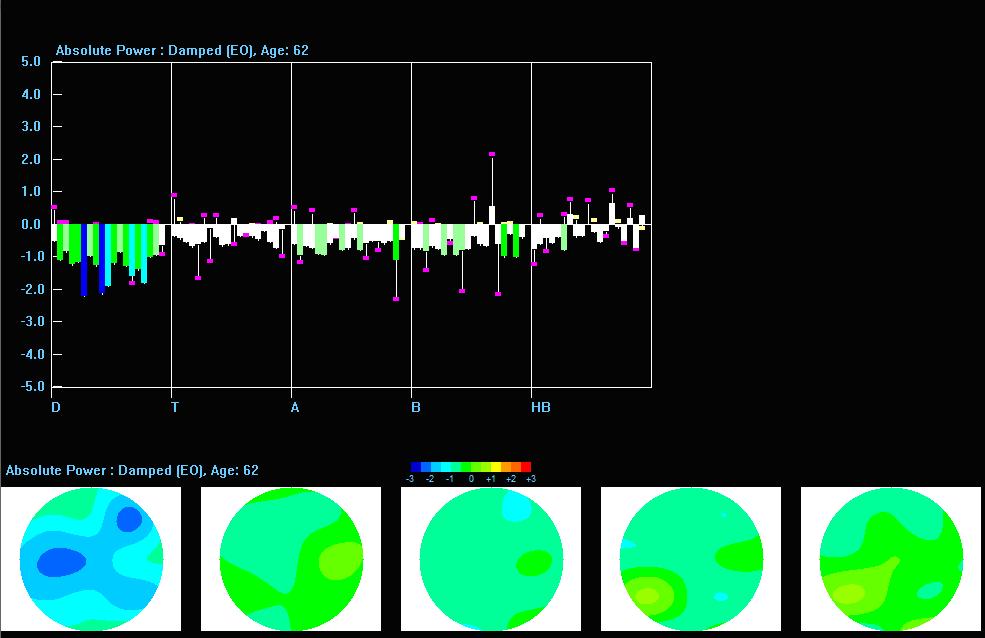

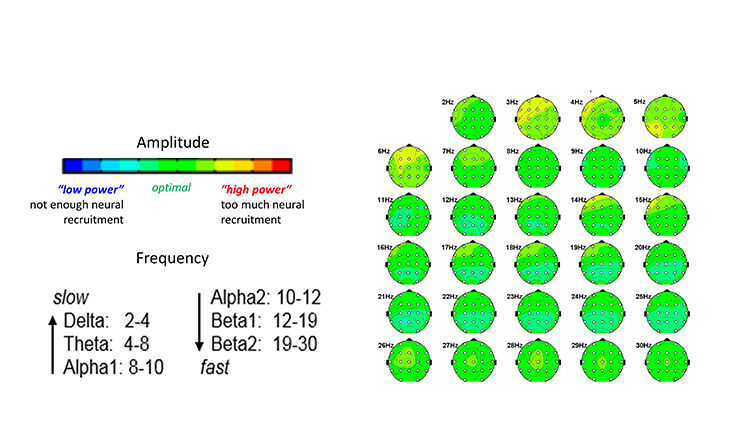

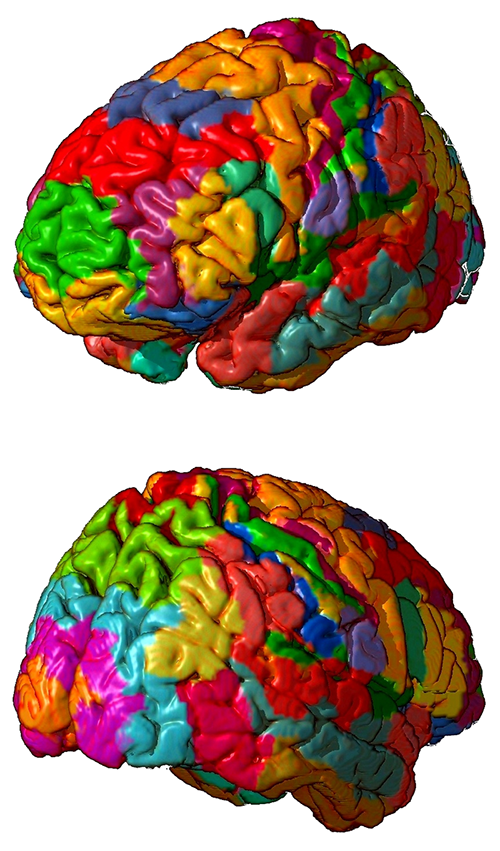

Quantitative EEG

Quantitative EEG methods include the ability to compare EEG recordings to reference database samples. Some reference groups are considered “normal” while others used are a sample of patients that may not be considered a good reference since by definition they are seeking medical care assumably for brain related conditions. Other reference groups consist of special operations military groups or sports teams, in other words are peer-reference groups from which to compare.Having a reference group allows for comparison statistics like z-scores. Most all professional use neurofeedback software can now permit any number of frequency bands or all frequencies to be modulated in the direction of a z-score of 0. The z-scores can represent frequency amplitude or coherence values (Thatcher et al., 2020). Graphic © Peter Hermes Furian/Shutterstock.com.

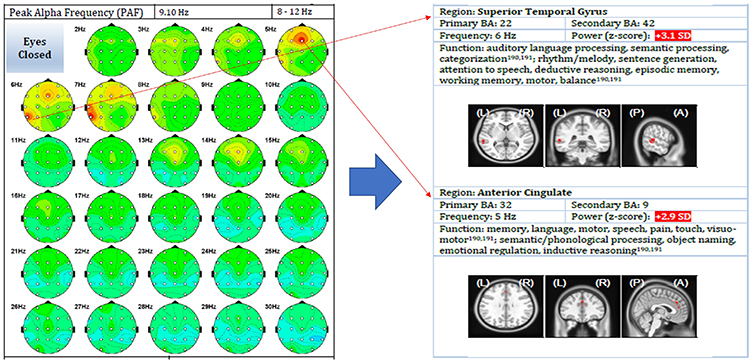

LORETA and Brodmann Area Training

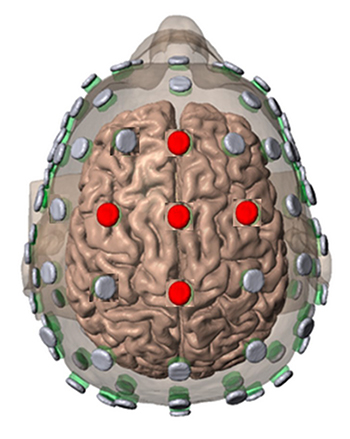

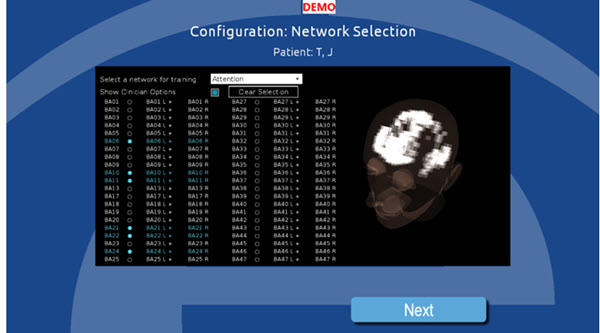

This approach can also include z-score measures and may in some cases be of some advantage over surface EEG neurofeedback. LORETA-guided neurofeedback allows a degree of focality to brain regions of interest (e.g., Brodmann Areas) to be the target of the feedback. The only additional consideration is that LORETA calculations require upwards of at least 16 scalp sensor connections, whereas surface z-score training can use a single active channel location (e.g., CZ). Individual athletes may have a specific area of interest to enhance, and this can be achieved with LORETA. Graphic © Sinauer.

Evolution of Neurofeedback Training Protocols for Optimal Performance

Difficulties with establishing the efficacy of a particular behavioral intervention have been covered in the Research Evidence Basis for Neurofeedback section. However, it is helpful to note that this review article (Monderer et al., 2002) cites multiple research studies that utilized treatments other than the sensorimotor rhythm training, including slow cortical potential training, training to inhibit epileptiform activity in the EEG and several other techniques. They also did not evaluate specific training approaches and whether interventions were applied appropriately. In light of Strehl (2014), it appears clear that simply using operant conditioning techniques without appropriate additional components noted in her paper may result in reduced effectiveness for otherwise helpful treatment.

In an attempt to elucidate the factors associated with effective neurofeedback training, Rogala and colleagues (2016) identify some of the do's and don’ts of effective neurofeedback training. Included in the list of approaches with positive effects is using more specific electrode locations chosen to be associated with known sources of the particular EEG frequency activity being trained, for example, frontal midline theta or posterior alpha activity.

The use of multiple electrodes in the general area identified as a source of this activity is also recommended to represent the source areas more completely. They suggest that neurofeedback trainers and researchers should identify optimal training electrode locations based on anatomical and functional studies and develop protocols that may use a weighted average approach for the input from various electrode locations.

Suggestions from the same paper of what not to do include avoiding training multiple EEG frequencies simultaneously to avoid confusion and cross-frequency interactions that may result in effects other than those desired for the training protocol. This suggestion did not have much basis in research and was merely an observation that studies involving multiple frequencies appeared to have less robust effects.

Ultimately Rogala and colleagues found that lack of specificity in the training approach seemed to elicit less clear and easily measurable results. However, they did not conclude that improved behavioral results were attributable to this narrower and easily measured focus, making their attempts to define the best approach somewhat inconclusive.

So, how do new practitioners learn the prevailing neurofeedback approaches? There are many perspectives in neurofeedback with sometimes widely varied methods, types of equipment, clinical populations, etc. In clinical practice, individuals providing neurofeedback training generally choose their training protocols based upon instructions from trainers and mentors, and therefore their approaches reflect these influences. In light of what may be considered a type of apprenticeship approach to the study of neurofeedback, which is a common entry point for new practitioners, it is worth discussing the various schools of neurofeedback training and how they have evolved and contributed to the development of the field of neurofeedback.

Glossary

ABA reversal design: a small N design where a baseline is followed by treatment and a return to baseline.

alpha blocking: the replacement of the alpha rhythm by low-amplitude desynchronized beta activity during movement, attention, mental effort like complex problem-solving, and visual processing.

alpha rhythm: 8-12-Hz activity that depends on the interaction between rhythmic burst firing by a subset of thalamocortical (TC) neurons linked by gap junctions and rhythmic inhibition by widely distributed reticular nucleus neurons. Researchers have correlated the alpha rhythm with relaxed wakefulness. Alpha is the dominant rhythm in adults and is located posteriorly. The alpha rhythm may be divided into alpha 1 (8-10 Hz) and alpha 2 (10-12 Hz).

alpha spindles: trains of alpha waves that are visible in the raw EEG and are observed during drowsiness, fatigue, and meditative practice.

amplitude: the strength of the EMG signal measured in microvolts or picowatts.

beta rhythm: 12-38-Hz activity associated with arousal and attention generated by brainstem mesencephalic reticular stimulation that depolarizes neurons in the thalamus and cortex. The beta rhythm can be divided into multiple ranges: beta 1 (12-15 Hz), beta 2 (15-18 Hz), beta 3 (18-25 Hz), and beta 4 (25-38 Hz).

beta spindles: trains of spindle-like waveforms with frequencies that can be lower than 20 Hz but more often fall between 22 and 25 Hz. They may signal ADHD, especially with tantrums, anxiety, autistic spectrum disorders (ASD), epilepsy, and insomnia.

bipolar (sequential) montage: a recording method that uses two active electrodes and a common reference.

common-mode rejection (CMR): the degree by which a differential amplifier boosts signal (differential gain) and artifact (common-mode gain).

delta rhythm: 0.05-3 Hz oscillations generated by thalamocortical neurons during stage 3 sleep.

desynchrony: pools of neurons fire independently due to stimulation of specific sensory pathways up to the midbrain and high-frequency stimulation of the reticular formation and nonspecific thalamic projection nuclei.

EEG activity: a single wave or series of waves.

epileptiform activity: spikes and sharp waves associated with seizure disorders.

Fast Fourier Transform (FFT): a mathematical transformation that converts a complex signal into component sine waves whose amplitude can be calculated.

frequency: the number of complete cycles that an AC signal completes in a second, usually expressed in hertz.

hertz (Hz): a unit of frequency measured in cycles per second.

infra-low-frequencies (ILF): frequencies below 0.1 Hz.

infra-slow-frequencies (ISF): frequencies below 0.1 Hz.

low resolution electromagnetic tomography (LORETA): Pascual-Marqui's (1994) mathematical inverse solution to identify the cortical sources of 19-electrode quantitative data acquired from the scalp.

posterior dominant rhythm (PDR): the highest-amplitude frequency detected at the posterior scalp when eyes are closed.

power: the amplitude squared and may be expressed as microvolts squared or picowatts/resistance.

protocol: a rigorously organized plan for training.

Quantitative EEG (qEEG): digitized statistical brain mapping using at least a 19-channel montage to measure EEG amplitude within specific frequency bins.

raw EEG signal: oscillating electrical potential differences detected from the scalp.

reference electrode: an electrode placed on the scalp, earlobe, or mastoid.

sampling rate: the number of times per second that an ADC samples the EEG signal.

sensorimotor rhythm (SMR): 13-15 Hz spindle-shaped sensorimotor rhythm (SMR) detected from the sensorimotor strip when individuals reduce attention to sensory input and reduce motor activity.

sleep spindles: waves that range from 12-15 Hz and last from 0.5 to several seconds widely distributed over the scalp and are observed during Stage 2 and 3 sleep.

standardized LORETA (sLORETA): a refinement of LORETA that estimates each voxel's electrical potentials without regard to their frequency, expresses normalized F-values, and achieves a 1-cubic-cm resolution.

surface Laplacian (SL) analysis: a family of mathematical algorithms that provide two-dimensional images of radial current flow from cortical dipoles to the scalp.

swLORETA: a more precise and accurate iteration of the LORETA source localization method.

theta/beta ratio (T/B ratio): the ratio between 4-7 Hz theta and 13-21 Hz beta, measured most typically along the midline and generally in the anterior midline near the 10-20 system location Fz.

theta rhythm: 4-8-Hz rhythms generated a cholinergic septohippocampal system that receives input from the ascending reticular formation and a noncholinergic system that originates in the entorhinal cortex, which corresponds to Brodmann areas 28 and 34 at the caudal region of the temporal lobe.

z-score training: neurofeedback protocol that reinforces in real-time closer approximations of client EEG values to those in a normative database.

References

Arns, M. W., Kleinnijenhuis, M., Fallahpour, K., & Breteler, M. H. . (2008). Golf performance enhancement by means of ‘real-life neurofeedback’ training based on personalized event-locked EEG profiles. Journal of Neurotherapy, 11(4), 11-18. https://doi.org/10.1080/10874200802149656

Ayers, M. E. (1977). EEG Neurofeedback to bring individuals out of Level Two Coma [Abstract]. Biofeedback and Self-Regulation, 20(3), 304–305.

Beauchamp, M. K., Harvey, R. H., & Beauchamp, P. H. (2012). An integrated biofeedback and psychological skills training program for Canada's Olympic short-track speedskating team. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology, 6(1), 67–84. https://doi.org/10.1123/jcsp.6.1.67

Berger, H. (1929). Über das elektroenkephalogramm des menschen. Arch Psychiatr Nervenkr 87(1), 527–570.

Budzynski, T.H. (1973). Sonic applications of biofeedback produced twilight states. In D. Shapiro, & T. Barber et al. (Eds.). Biofeedback and self-control. Aldine Publishing Company.

Budzynski, T. H. (1977). Tuning in on the twilight zone. Psychology Today, 11, 38–44.

Budzynski, T. H. (1996). Brain brightening: Can neurofeedback improve cognitive process? Biofeedback, 24, 14–17.

Byers, A. P. (1998). Neurotherapy reference library (2nd ed.). Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback.

Campos da Paz, V. K., Garcia, A., Campos da Paz Neto, A., & Tomaz, C. (2018). SMR neurofeedback training facilitates working memory performance in healthy older adults: A behavioral and EEG study. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 12, 321. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2018.00321

Cheng, M. Y., Huang, C. J., Chang, Y. K., Koester, D., Schack, T., & Hung, T. M. (2015). Sensorimotor rhythm neurofeedback enhances golf putting performance. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 37(6), 626–636. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.2015-0166

Doppelmayr, M., & Weber, E. (2011). Effects of SMR and theta/beta neurofeedback on reaction times, spatial abilities, and creativity. Journal of Neurotherapy, 15(2), 115-129. https://doi.org/10.1080/10874208.2011.570689

Evans, J. R., Dellinger, M. B., & Russell, H. L. (Eds.) (2020). Neurofeedback: The first fifty years. Academic Press.

Fehmi, L. G., & Robbins, J. (2008). Sweet surrender-Discovering the benefits of synchronous alpha brainwaves (pp. 231-254). Measuring the immeasurable: The scientific case for spirituality. Sounds True, Inc.

Fein, G., Galin, D., Johnstone, J., Yingling, C. D., Marcus, M., & Kiersch, M. E. (1983).EEG power spectra in normal and dyslexic children. I. Reliability during passive conditions. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol, 55(4), 399-405. https://doi.org/10.1016/0013-4694(83)90127-x

Green, E. E., Green, A. M., & Walters, E. D. (1970). Voluntary control of internatial states: Psychological and physiological. Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 9(1), 1–26.

Hardt, J. V., & Kamiya, J. (1978). Anxiety change through electroencephalographic alpha feedback seen only in high anxiety subjects. Science, 201(4350), 79-81. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.663641 PMID: 663641.

John, E. R., Ahn, H., & Prichep, L., Trepetin, M., Brown, D., & Kaye, H. (1980). Developmental equations for the electroencephalogram. Science, 210(4475), 1255-1258. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.7434026

Johnstone, J. & Gunkelman, J. (2003). Use of databases in QEEG evaluation. Journal of Neurotherapy, 7, 3-4, 31-52. https://doi.org/10.1300/J184v07n03_02

Kamiya, J. (1968). Conscious control of brain waves. Psychology Today, 1, 56-60.

Legarda, S. B., McMahon, D., Othmer, S., & Othmer S. (2011). Clinical neurofeedback: Case studies, proposed mechanism, and implications for pediatric neurology practice. J Child Neurol., 26(8),1045-1051. https://doi.org/10.1177/0883073811405052

Leong, S. L., Vanneste, S., Lim, J., Smith, M., Manning, P., & De Ridder, D. (2018). A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled parallel trial of closed-loop infraslow brain training in food addiction. Sci Rep 8(11659). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-30181-7

Lubar, J. F., & Bahler, W. W. (1976). Behavioral management of epileptic seizures following EEG biofeedback training of the sensorimotor rhythm. Biofeedback Self Regul, 1(1), 77-104. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00998692. PMID: 825150.

Lubar, J. O., & Lubar, J. F. (1984). Electroencephalographic biofeedback of SMR and beta for treatment of attention deficit disorders in a clinical setting. Biofeedback and Self-Regulation, 9(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00998842

Lubar, J. F., Shabsin, H. S, Natelson, S. E., Holdson, S. E., Holder, G. S., Whittsett, S. F., Pamplin, W. E., & Krulikowski, D. I. (1981). EEG operant conditioning in intractable epileptics. Archives of Neurology, 38, 700–704.

Lubar, J. F., & Shouse, M. N. (1976). EEG and behavioral changes in a hyperkinetic child concurrent with training of the sensorimotor rhythm (SMR): A preliminary report. Biofeedback Self Regul,1(3), 293-306. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01001170. PMID: 990355.

Marzbani, H., Marateb, H. R., & Mansourian, M. (2016). Neurofeedback: A comprehensive review on system design, methodology and clinical applications. Basic and clinical neuroscience, 7(2), 143–158.

Monastra, V. J., Lubar, J. F., Linden, M., VanDeusen, P., Green, G., Wing, W., Phillips, A., & Fenger, T. N. (1999). Assessing attention deficit hyperactivity disorder via quantitative electroencephalography: An initial validation study. Neuropsychology, 13(3), 424–433. https://doi.org/10.1037/0894-4105.13.3.424

Nuwer, M. R., & Coutin-Churchman, P. (2014). Brain mapping and quantitative electroencephalogram. Encyclopedia of the Neurological Sciences (2nd ed.). Elsevier.

Oken, B. S., & Chiappa, K. H. (1988). Short-term variability in EEG frequency analysis. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol, 69, 191–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/0013-4694(88)90128-9

Peniston, E. G., & Kulkosky, P. J. (1989). Alpha-theta brain wave training and beta-endorphin levels in alcoholics. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 13, 271 – 279. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1530-0277.1989.TB00325.X

Peniston, E. G., & Kulkosky, P. J. (1990). Alcoholic personality and alpha-theta brain wave training. Medical Psychotherapy, 3, 37–55.

Peniston, E., Marrinan, D., Deming, W., & Kulkosky, P. (1993). EEG alpha-theta brainwave synchronization in Vietnam theatre veterans with combat-related post-traumatic stress disorder and alcohol abuse. Advances in Medical Psychotherapy, 6, 37-49.

Putman, J. A., Othmer, S. F., Othmer, S., & Pollock, V. E. (2005). TOVA results following inter-hemispheric bipolar EEG training. Journal of Neurotherapy: Investigations in Neuromodulation, Neurofeedback and Applied Neuroscience, 9(1), 37-52. https://doi.org/10.1300/J184v09n01_04

Raymond, J., Varney, C., Parkinson, L. A., & Gruzelier, J. H. (2005). The effects of alpha/theta neurofeedback on personality and mood. Brain research. Cognitive brain research, 23(2-3), 287–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cogbrainres.2004.10.023

Ribas, V. R., Ribas, R., & Martins, H. (2016). The learning curve in neurofeedback of Peter Van Deusen: A review article. Dementia & Neuropsychologia, 10(2), 98–103. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1980-5764-2016DN1002005

Rogala, J., Jurewicz, K., Paluch, K., Kublik, E., Cetnarski, R., & Wróbel, A. (2016). The do's and don'ts of neurofeedback training: A review of the controlled studies using healthy adults. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 10, 301. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2016.00301

Scott, W. C., Kaiser, D., Othmer, S., & Sideroff, S. I. (2005). Effects of an EEG biofeedback protocol on a mixed substance abusing population. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 31(3), 455–469. https://doi.org/10.1081/ada-200056807

Sherlin, L., Ford, L., Baker, A., & Troesch, J. (2015). Observational report of the effects of performance brain training in collegiate golfers. Biofeedback, 43, 64-72. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-43.2.06

Shouse, M. N., & Lubar, J. F. (1979). Operant conditioning of EEG rhythms and ritalin in the treatment of hyperkinesis. Biofeedback and Self-Regulation, 4, 299–312. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00998960

Sittenfeld, P., Budzynski, T., & Stoyva, J. (1976). Differential shaping of EEG theta rhythms. Biofeedback and Self-Regulation, 1, 31–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00998689

Smith, M. L., Collura, T. F., Ferrara, J., & de Vries, J. (2014). Infra-slow fluctuation training in clinical practice: A technical history. NeuroRegulation, 1(2), 187–207. https://doi.org/10.15540/nr.1.2.187

Smith, M. L., Leiderman, L., & de Vries, J. (2017). Infra-slow fluctuation (ISF) for autism spectrum disorders. In T. F. Collura & J. A. Frederick (Eds.), Handbook of clinical QEEG and neurotherapy. Routledge Taylor and Francis Group.

Sterman, M. B. (1976). Effects of brain surgery and EEG operant conditioning on seizure latency following monomethylhydrazine in the cat. Exp. Neurol., 50, 757-765. https://doi.org/10.1016/0014-4886(76)90041-8

Sterman M. B. (1996). Physiological origins and functional correlates of EEG rhythmic activities: implications for self-regulation. Biofeedback and Self-Regulation, 21(1), 3–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02214147

Sterman, M. B., & Friar, L. (1972). Suppression of seizures in an epileptic following sensorimotor EEG feedback training. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol,33(1), 89-95. https://doi.org/10.1016/0013-4694(72)90028-4. PMID: 4113278

Sterman, M. B., Howe, R. C., & Macdonald, L. R. (1970). Facilitation of spindle-burst sleep by conditioning of electroencephalographic activity while awake. Science, 167(3921), 1146–1148. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.167.3921.1146

Sterman, M. B., Lopresti, R. W., & Fairchild, M. D. (1969). Electroencephalographic and behavioral studies of monomethylhydrazine toxicity in the cat. AMRL-TR-69-3, Aerospace Medical Research Laboratory, Air Force Systems Command, Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Ohio.

Sterman, M. B., LoPresti, R. W., & Fairchild, M. D. (2010). Electroencephalographic and behavioral studies of monomethyl hydrazine toxicity in the cat. Journal of Neurotherapy, 14(4), 293-300, https://doi.org/10.1080/10874208.2010.523367

Strehl, U. (2014). What learning theories can teach us in designing neurofeedback treatments. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 8(894).

Swingle, P. (2014). Clinical versus normative databases: Case studies of clinical Q assessments. NeuroConnections.

Thatcher, R. W. (1998). Normative EEG databases and EEG biofeedback. Journal of Neurotherapy, 2(4), 8-39. https://doi.org/10.1300/J184v02n04_02

Thatcher, R. W., Biver, C. J., Soler, E. P., Lubar, J., & Koberda, J. L. (2020). New advances in electrical neuroimaging, brain networks and neurofeedback protocols. J. Neurol. Neurobiol., 6, 168. https://doi.org/10.16966/2379-7150.168

Thatcher, R. W., Lubar, J. F., & Koberda, J. L. (2019). Z-Score EEG biofeedback: Past, present, and future. Biofeedback, 47(4), 89–103. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-47.4.04

Thompson, L., & Thompson, M. (1998). Neurofeedback combined with training in metacognitive strategies: effectiveness in students with ADD. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 23(4), 243–263. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1022213731956

Thompson, T., Steffert, T., Ros, T., Leach, J., & Gruzelier, J. (2008). EEG applications for sport and performance. Methods, 45(4), 279–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymeth.2008.07.006

Wilson, V., Peper, E., & Moss, D. (2006) “The Mind Room” in Italian soccer training: The use of biofeedback and neurofeedback for optimum performance. Biofeedback, 34, 79-81.

D. INTRODUCTION TO ALPHA-THETA TRAINING

The EEG biofeedback (neurofeedback) approach known as alpha-theta (A-T) training is historically one of the first to be developed and is also one of the most widely used. This section will describe the evolution from early alpha training efforts to the current refinements and give an overview of the research and application of this approach. A demonstration of an A-T training session and various graphics will help readers grasp the concepts and outcomes of this type of training.

This section covers Underlying Theory, Cross-Frequency Synchronization, Local Field Potential, Global and Local Synchronization, History and Development, Benefits of A-T Training, Comparison of Interventions, A-T Training Protocols, Expected Results, Applications, Cautions (e.g., abreactions), Self-Medication, Substance/Behavioral Use Disorders, and Final Thoughts.

Underlying Theory -- Timing is Everything!

Oscillatory timing is the brain's fundamental organizer of neuronal information. According to Buzsaki (2006), brain activity is associated with multiple nested rhythms that emerge from integrated and coordinated activity mediated by small-world networks that interact with each other through hubs and nodes.

Cross-Frequency Synchronization

Slower frequencies organize and provide a matrix within which faster frequencies can function in a coordinated manner. Faster frequencies emerge from “bound networks” (Gunkelman, 2005), meaning that as networks responsible for slower, rhythmic frequencies become synchronized or bound together, faster frequencies emerge due to neuronal activity arising from these bound networks. Scalp EEG frequencies represent the synchronized firing of multiple neurons. The more neurons firing synchronously at a given frequency, the higher the voltage (amplitude) of that frequency.

For example, when the eyes are open, visual processing systems made up of millions of neurons are busy responding to incoming sensory input from the thalamocortical relay (TCR) system that involves ascending pathways from the thalamus mediated by the reticular nucleus of the thalamus (nRt). When the eyes are closed and visual input is no longer present, the visual processing neurons respond to a rhythmic signal, coming from the TCR system that results from interactions between the thalamus and the nRt, which also respond to ascending neurochemical inputs from the brainstem and reticular activating system (Cox et al., 1997).

This rhythm is commonly called the alpha rhythm (Berger, 1929) or the posterior dominant rhythm (PDR). When visual neurons collectively fire in response to this rhythmic input from the thalamus, the amplitude of the alpha signal increase.

This is called the alpha response.

Visual neurons begin to process the incoming information relayed by the TCR system when the eyes are opened. So fewer neurons are responding to the rhythmic PDR input, and the amplitude of alpha measured from the scalp decreases.

This is known as alpha blocking.

The same number of neurons may still be active, but since they are now functioning more independently and each grouping of neurons has a separate task, the overall voltage of the EEG as a whole decreases. Reduced synchrony of neuronal firing results in decreased amplitude.

Benefits of A-T Training

Research participants reported "transformative" experiences, including:

Spiritual and religious imagery

Memory recall experiences

Insight into personal behaviors and patterns

Changes in interpersonal relationships

Understanding of purpose

Resolution of long-standing anxiety and depression

Release of trauma responses and reactivity

Improved self-esteem /self-image

Abstinence from substance and behavioral addictions

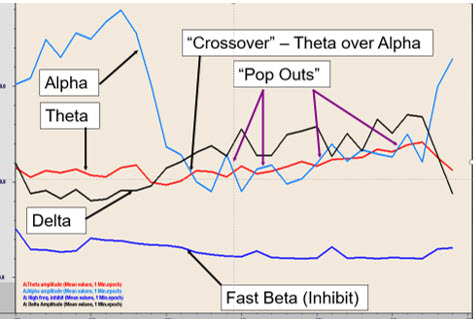

The auditory feedback to the trainee is that of reward when theta power increases over alpha. This is called a “crossover” since it is a transition from the common baseline state of dominant alpha to that of theta. The sensation for the trainee is a sense of floating, or twilight state felt just before falling asleep. It is also an EEG pattern commonly produced with hypnosis and deep relaxation. [34-38]. The relaxation state is enhanced when the trainee can increase and maintain for several minutes theta power over alpha power by 1mV and maintain reduced beta. Sensor placement at parietal and occipital locations is used, and training is with eyes closed. The procedure more often produces visual memories (Johnson, 2013).

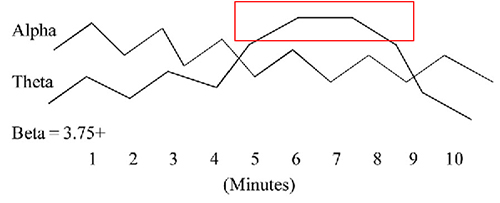

One of the performance benefits of synchronized theta activity (4-7 Hz) is encoding new information or working memory. It is also applied as a cognitive training routine in pre-performance preparations using imagery (e.g., dance performance; Gruzelier, 2014). Military applications might include freefall training, movement to contact, and equipment assembly, to name a few. Whether in performing arts, professional sports, or even among business executives, the neurofeedback application of aiding a calm and memory-enhanced brain state has grown in use among sports psychologists (Harmison, 2006). Increased theta activity is highlighted by the red box shown below.

Comparison of Interventions

Patricia Norris, Steven Fahrion, and others split off from the Menninger Foundation in 1993 to form the Life Sciences Institute of Mind-Body Health. They conducted a 5-year study of A-T training in a prison population (described in Norris, 2017).

Two groups of participants all received the following self-regulation, educational and supportive components of the study: Temperature training, breath training, didactic presentations on philosophy, psychodynamic aspects of self, and psychosynthesis exercises. Participants were treated with “deference, respect, and compassion.” One group also received 45 daily sessions of A-T neurofeedback training.

The results of a 2-year follow-up of participants (N = 35) showed encouraging results compared to standard substance use disorder (SUD) treatment in prison environments, typically with 10-20% "survival" rates defined by abstinence, no violations, and no criminal activity.

At a 1-year follow-up, 78% of the A-T group survived compared with 75% of controls. At a 2-year follow-up, 69% of the A-T group survived compared with 64% of the control group.

Younger participants had somewhat different results, suggesting that the A-T training was a more critical component for this group. At a 1-year follow-up, the A-T group had a 74% survival rate compared to 54% for controls. At a 2-year follow-up, the A-T group had a 60% survival rate compared with 45% for controls.

African-American and Hispanic participants also had results suggesting improved results with A-T training. At a 1-year follow-up, the A-T group had a 70% survival rate compared to 48% for controls. At a 2-year follow-up, the A-T group had a 48% survival rate compared with 40% for controls.

What Was the Mechanism of Change?

This study shows that the overall treatment program was quite effective compared to standard interventions. The difference between A-T and control group results was not statistically significant when the groups were viewed as a whole. However, age and ethnicity functioned as moderator variables.The overall design and implementation of the program was likely the most crucial aspect, and the A-T training was one effective component of that broader effort.

The relationship between the trainer and the client is one of the most important components of any intervention.

This is particularly critical when providing A-T training because the desirable state identified as the crossover state requires complete trust on the part of the client so that they can let go of emotional, psychological, and physical defenses that would prevent them from allowing the type of disconnection from outside sensory input necessary for the state to occur.

Trainers must work to engender this trusting relationship before implementing A-T training. This is one reason why many trainers use a variety of additional interventions before and/or concurrently with A-T training.

Some of those interventions include:

Breathing, including heart rate variability (HRV) training

Guided relaxation

Peripheral temperature training

EMG biofeedback

Electrodermal biofeedback

SMR, beta, and other amplitude-based neurofeedback protocols

Z-score based neurofeedback approaches

Hypnotic inductions

Behavior change scripts and suggestions

Post-session psychotherapy, processing, and interpretation

What Role Does A-T Training Play in the Changes Experienced By Clients?

The client’s ability to enter the desired state may depend upon many factors: set and setting, expectations, trainer self-training, and interpersonal skills.The ability to enter the reverie state appears to result in significant opportunities for change, which can also occur from multiple interventions such as:

Mindfulness meditation

Biofeedback, including HRV training

A-T training

Other types of EEG biofeedback

Other self-help and behavior change interventions such as hypnosis and psychotherapy

Interventions that lead to desirable states appear to have one thing in common – it is difficult for the client or student to know when they are in the state, getting close to the state, or very far away from the state.

A-T neurofeedback, when done correctly, provides constant information about where one is on the continuum. This allows the client to move toward and experience the desired state more quickly and facilitates faster and more accurate skill acquisition.

A-T Training Protocols

A variety of approaches to A-T training have been developed. The initial protocol developed by Eugene Peniston (Peniston, 1989, 1990) involved two separate audio tones: alpha amplitude and the other representing theta amplitude. When alpha amplitude increased, the alpha tone occurred more frequently, and when theta amplitude increased, the theta tone occurred more often. In this way, the trainee could perceive the relative amount (amplitude or voltage) of each frequency band and could practice various strategies to accomplish this task to increase theta and decrease alpha. The feedback guided the trainee and reinforced the desired state change behavior, resulting in the so-called crossover state.

Some trainers have found this protocol somewhat complicated to administer. Peniston prescribed threshold changes to elicit a shift to the crossover state, beginning with a setting that rewarded alpha 50 to 70% of the time and rewarded theta approximately 20 to 40% of the time. As training progressed, the percentage of the alpha reward tone was allowed to decrease as the signal amplitude decreased. In contrast, the theta reward tone was allowed to increase if the theta amplitude increased. However, the instruction was to maintain the theta reward tone at approximately 40%, even if the voltage decreased, to provide at least that minimal level of positive reinforcement.

Some practitioners attempting to train clients with this approach found this difficult to administer correctly, and some clients became confused about the desired signal. Subsequently, a simplified and widely-used approach was developed that utilizes the theta-alpha ratio to simplify the training protocol and provide a single-tone feedback signal representing the crossover state. Often the trainee is provided with a tone or some other audio indicator that they have exceeded a certain threshold indicating that theta has increased in amplitude over alpha amplitude, suggesting that the crossover state has occurred.

This is a simple protocol that has been incorporated into a variety of commercial neurofeedback platforms developed by equipment and software manufacturers. Concerns about this simplified approach include the lack of specificity in the training protocol and the lack of feedback to inhibit undesirable changes in the EEG, leading to negative reactions and the lack of a well-defined goal.

The theta/alpha ratio is not precise since the band frequencies are quite broad. An increase in the slower theta component can increase the feedback reward signal but may not represent the desirable crossover state. Additionally, the client may not even produce typical alpha increases initially. Therefore, the simple ratio feedback approach lacks the precision to identify desirable states and differentiate between causal factors resulting in increases or decreases in positive feedback.

Finally, there is no indicator of whether the client is close to the goal, far away from the goal or somewhere in between. A single tone representing the crossover leaves the client wondering where they are on the continuum of alertness and awareness.

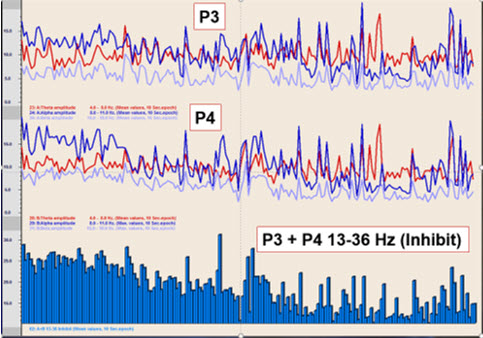

Targeted Training - 6-9 Hz

Following significant experimentation and clinical experience, John Anderson and others developed a protocol that involves training the frequency band from 6-9 Hz, which is the actual frequency band of the so-called crossover state. This frequency band straddles the standard 4-8 Hz theta and 8-12 Hz alpha frequency bands. This protocol is combined with an inhibit channel that prevents an increase in 2-6 Hz activity. When allowed to increase during A-T training, it results in an abreaction or negative reaction, sometimes involving traumatic recall or depersonalization experiences.Through experience, using the 2-6 Hz frequency band to inhibit this transition to a more sleep-like state appears to prevent these negative reactions. Additionally, a frequency band from approximately 13-36 Hz is used to prevent an increase in faster frequency EEG patterns associated with cognitive activity, thereby ensuring that the client remains in the relaxed reverie state without engaging in thinking and problem-solving activities. This does represent a somewhat more complex approach to the A-T training protocol but is more likely to produce a desirable outcome without the dangers of negative reactions or excessive cognitive activity.

Reward Feedback

Reward feedback is a proportional audio signal, usually music, that increases and decreases in volume in direct proportion to the changes in 6-9 Hz amplitude. Clients can select their audio from calming, relaxing musical choices.The volume changes in the audio selection allow the client to know continuously where they are on the continuum from a typical eyes-closed alert state to the deep reverie state associated with the optimum experience. This is similar to the hot/cold game played by children.

Inhibit Feedback

The low-frequency inhibit (2-6 Hz) feedback is a recording of birds chirping that only sounds above a set threshold and becomes louder as the amplitude of this signal increases. This allows the client to be gently alerted when shifting into this lower frequency state without being startled out of the desirable reverie state. Most clients associate birds chirping with waking up in the morning, so it seems to represent an intuitive indicator that is easy to remember.The high-frequency inhibit (10-36 Hz) is a recording of ocean wave sounds with an inverse proportional relationship to the amplitude of this signal. It becomes louder as the "busy brain" decreases, thus rewarding a decrease in cognitive activity. The ocean wave sound and the rewarding music blend to create a calming and reinforcing auditory environment that encourages the correct state while providing constant, meaningful feedback to guide the client.

Sample Training Session

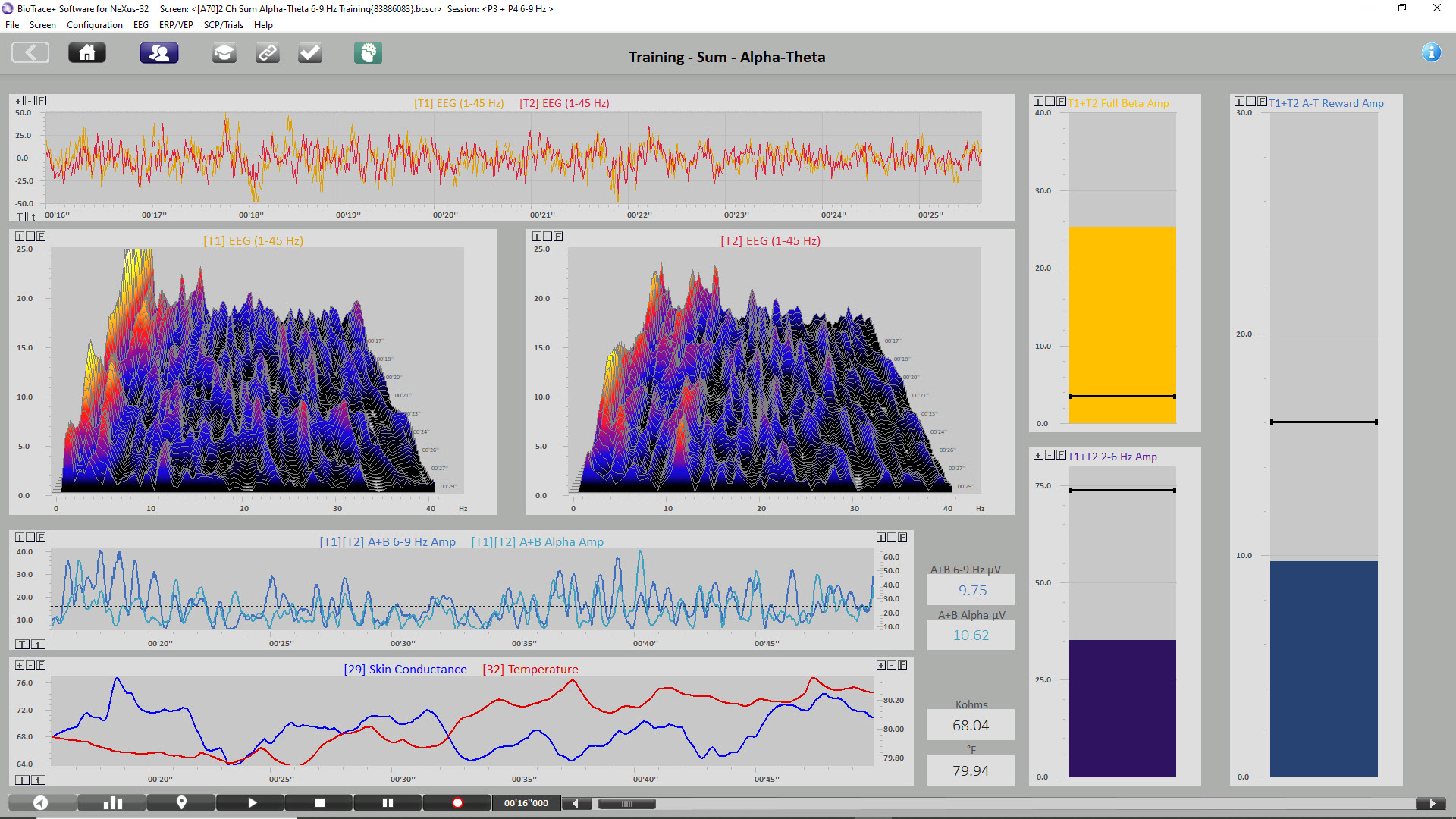

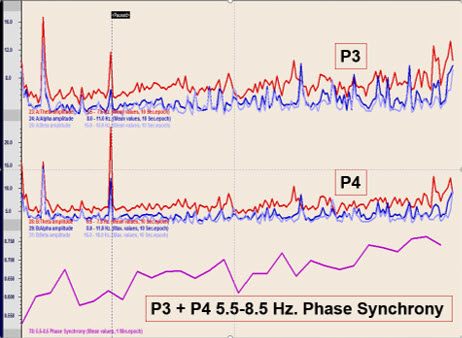

The image below shows the beginning of a 2-channel A-T training session. Note that the eyes closed EEG shows no clear posterior rhythm (alpha) and that peripheral skin temperature is 79.94o F measured from the small finger of the non-dominant hand, indicating increased SNS activity. GSR/SC is shown as resistance in Kohms, where higher values indicate decreased sweat gland activity measured from the palm of the non-dominant hand. Current GSR readings are 68.04 Kohms, which indicates increased arousal/anxiety. The sum of the P3 + P4 6-9 Hz activity is 9.75 μV, while 8-12 Hz alpha is 10.62 μV. Graphic © John S. Anderson.

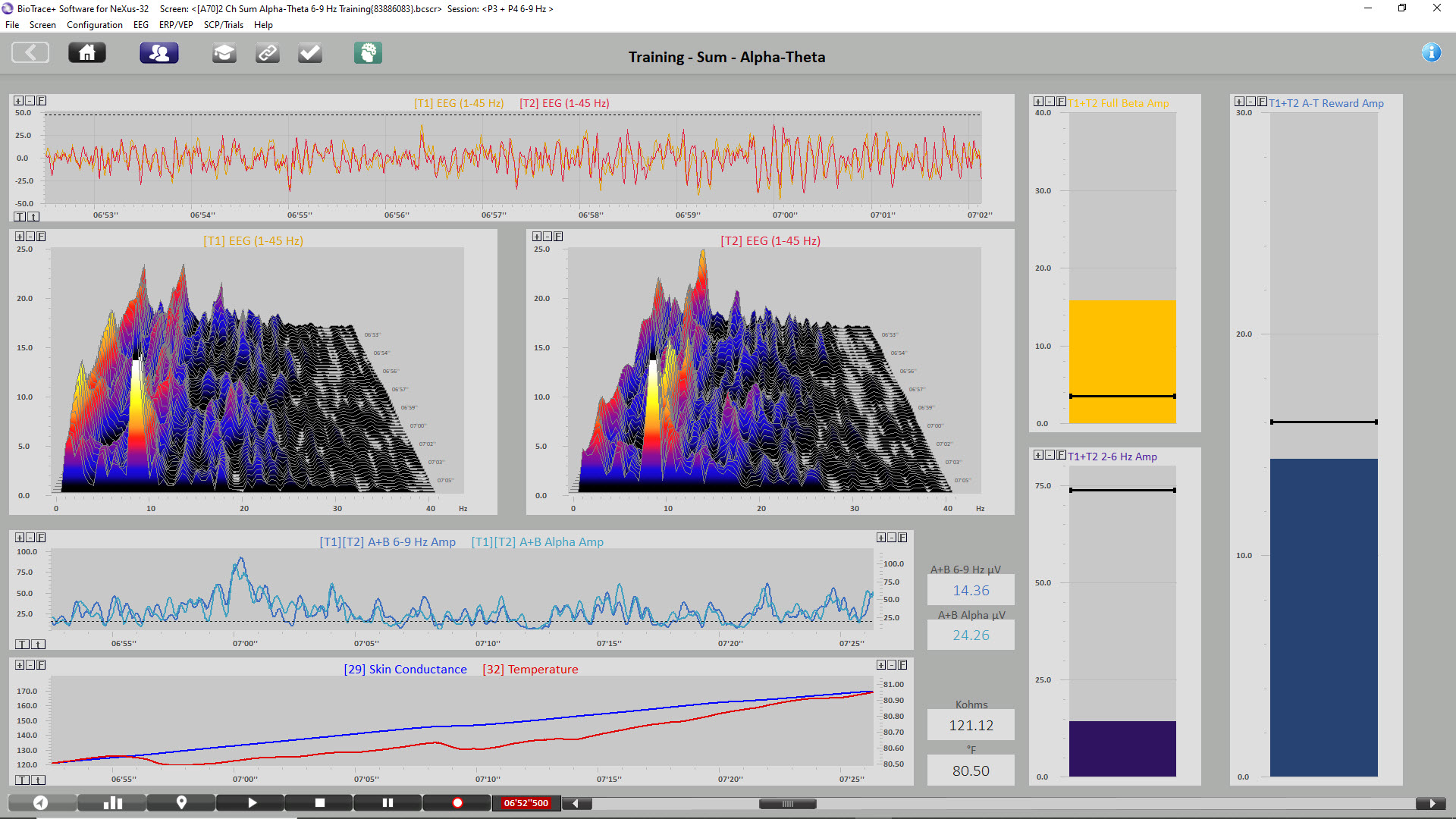

The image below shows the same session when the initial increase in alpha amplitude occurs. Peripheral skin temp has increased to 80.50o F, and GSR has increased to 121.12 Kohms, indicating decreased arousal. P3 + P4 6-9 Hz activity has increased to 14.34 μV, while 8-12 Hz alpha has increased to 24.26 μV. Graphic © John S. Anderson.

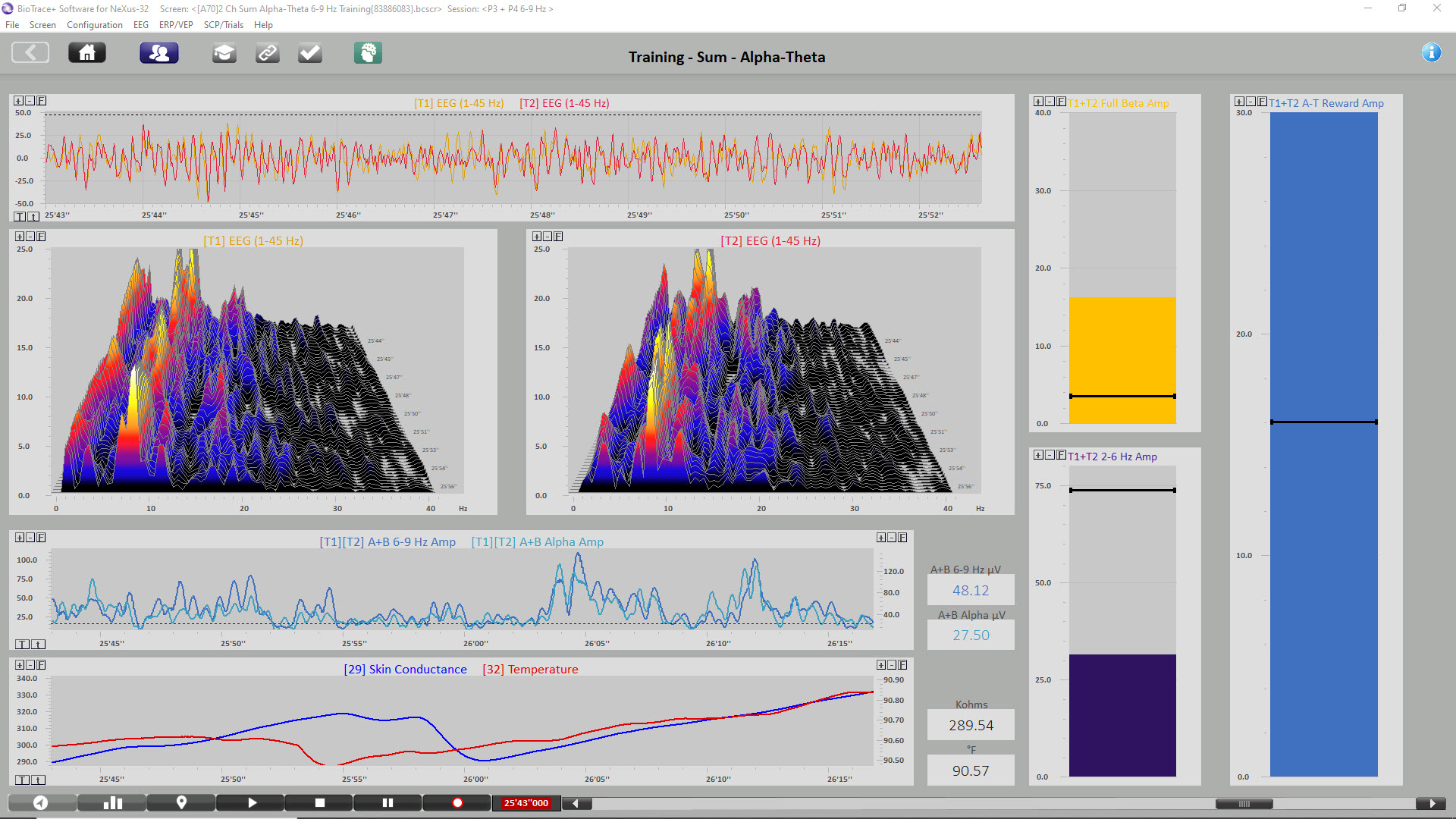

The image below shows the same session near the end. Peripheral skin temp has increased to 90.57

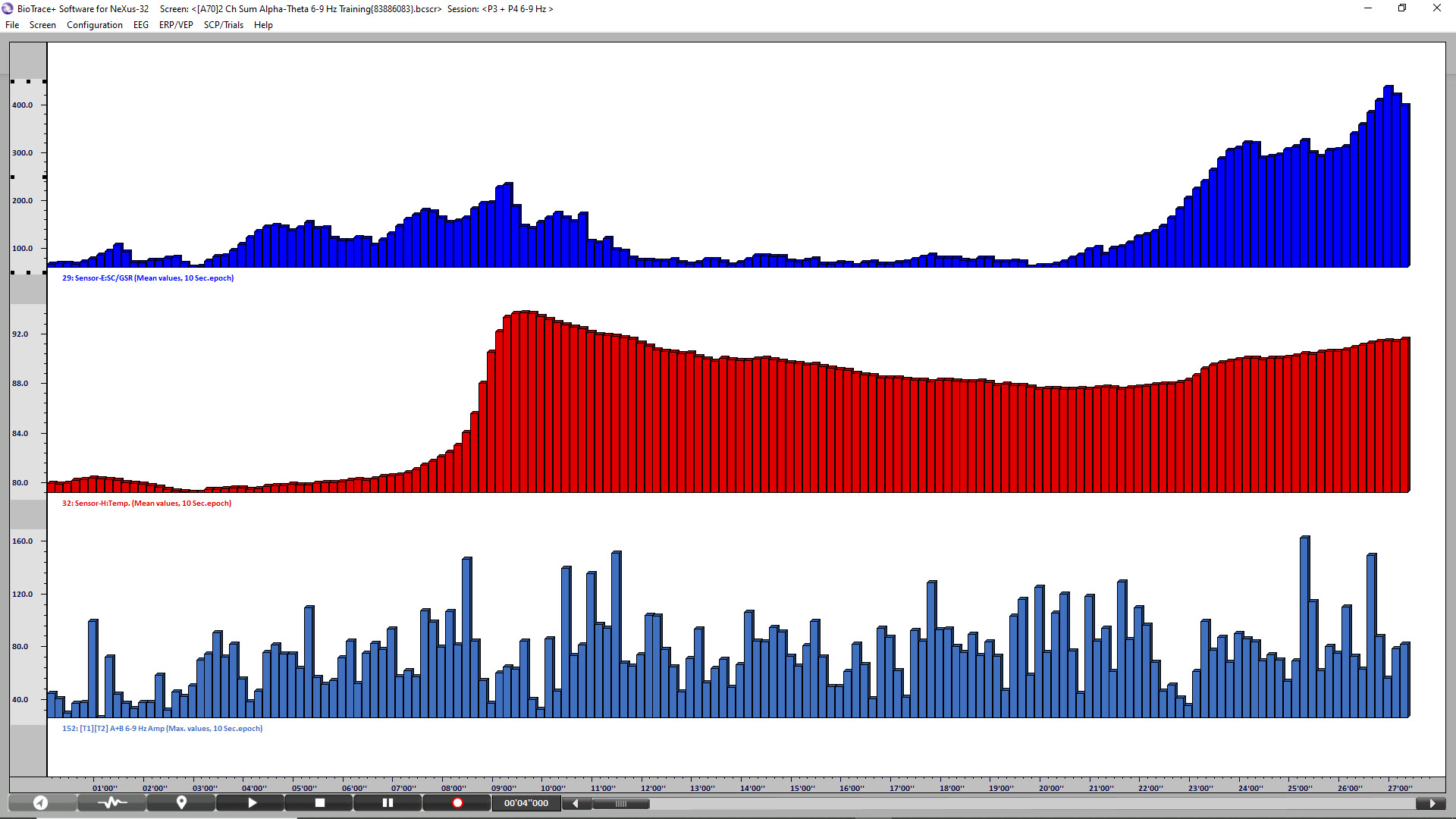

The final image is a summary screen that shows an increase in GSR (top), temperature (middle), and P3 + P4 6-9 Hz activity (bottom) across the session. Graphic © John S. Anderson.

Expected Results

This state encouraged by this training appears to be similar to that experienced during mindfulness meditation practice. The participant or trainee experiences what is sometimes called a witness state, or the observation of the flow of consciousness, memory, and internal thoughts, without actively pursuing these thoughts. This training approach operationalizes this training so that the client experiences indicators via audio rewards that encourage remaining in the state and discourage movement in either direction towards a deeper, more sleep-like state or an activated cognitive state.

Individuals participating in this training report increased receptiveness to suggestion, the experience of a reverie state, free association and/or consciousness streaming experiences, experiences of representational and/or symbolic/spiritual/religious imagery, and experiences of emotional resolution, insight, and understanding.

The theories associated with this approach suggest that this state of brain activity is similar to that experienced in hypnotic induction states and in deeply relaxed and light sleep states associated with memory consolidation.

Applications

Whatever the approach, A-T training has been utilized for a variety of different interventions, mostly falling into the loose categories of stress-related conditions (Nicholson et al., 2020; Peniston, 1989, 1990), addictive behavior (Burkett, 2005; Kaiser, 2005; Peniston, 1989, 1990) and optimal performance (Gruzelier, 2014).

An example of optimum performance training using A-T training can be seen in Gruzelier’s (2014) work with musicians in a study published in Biological Psychology. He demonstrated improvements in three music domains: creativity/musicality, technique, and communication/presentation. His study showed improvements in all blinded, independently rated scales for the alpha-theta training group compared to an additional EEG training group using an SMR (12-15 Hz) reward and a non-training control group.

Caption: John Gruzelier

These results demonstrated that the effect is specific to the type of training (i.e., the frequency band or reward) as the SMR training group while improving technical scores associated with attention and motor control, did not show the same improvement in the other scales. The study also showed improved ratings overall for A-T training compared to a control condition.

Cautions

Some neurofeedback providers (Thompson & Thompson, 2003) suggest A-T training be used in the context of clinical support when an individual is suspected to have experienced trauma or a trauma-related condition. Therefore, providers utilizing this intervention should have advanced training beyond introductory-level course work.

Caption: Michael and Lynda Thompson

As we have noted, much of this concern results from a lack of understanding of the process associated with this protocol and an incorrect application of the training, including a lack of appropriate indicators to the client regarding undesirable frequency activity.

Client preparation is essential, as is true with any intervention. Clients should be instructed to immediately inform the neurofeedback provider of any negative reactions so that corrective training and/or a calming intervention such as paced breath training via heart rate variability feedback can be implemented.

One of the characteristics of this training is a decrease in limbic system arousal. This is seen in decreased anxiety, easier transitions to sleep and deeper, more restful sleep, a long-term overall reduction of limbic system activation, insulation from the stress of daily life events, and improved state management and stability.

There is evidence that this state may also be similar to that identified in fMRI studies as the default mode network, sometimes known as the resting state network. This network of connections in the brain is associated with what is sometimes known as the self-referential state that accompanies a state of self-awareness associated with memory recall and non-directed cognition that appears strikingly similar to that described by individuals participating in A-T training.

The technical aspects of this type of training are specific to the training platform, and practitioners will need to familiarize themselves with their systems' specific software and hardware characteristics.

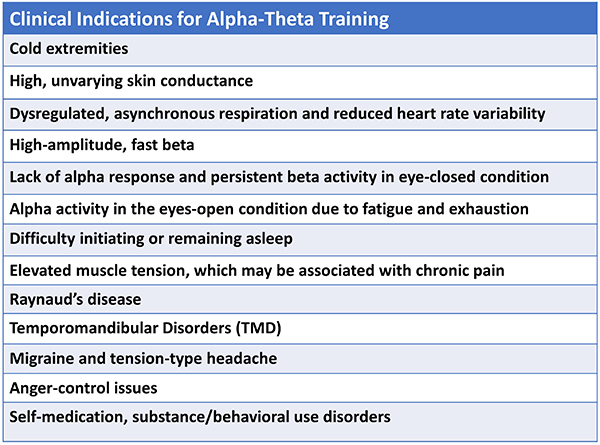

Typical indications for A-T training include clients with the following presenting symptoms.

Practitioners have used various pre-training options to facilitate their client’s ability to access the desirable state during A-T training. Peniston (1989, 1990) initially used 10 sessions of hand temperature training to criteria, which was 96°F. Scott and Kaiser (2005) used beta and SMR training to stabilize the nervous system before continuing A-T training. Other practitioners use heart rate variability training and/or a combination of training approaches depending on the client’s needs. Some optimal performance practitioners begin directly with A-T training, which may be their sole neurofeedback intervention.

Training protocols vary depending on the environment, the clientele, and the ability of the practitioner to provide sessions. Initially, Peniston used training sessions once per day for 30 sessions. Scott and Kaiser also used daily training sessions for 30 A-T training sessions. Other practitioners have used various approaches, including once or twice weekly sessions and some have utilized twice daily intensive training programs.

Peniston's (1989, 1990) initial approach used the O1 electrode location based on the 10-20 international electrode placement system. Subsequent practitioners have also utilized the Pz electrode location or the P3 and P4 electrode locations to facilitate two-channel A-T training.

Peniston’s approach to training included behavior change scripts that would be read to the participant before the training session. He also conducted post-session debriefing conversations with his participants (personal communication, 1995). Other practitioners have also used behavior change scripts or scenarios, affirmations, behavior change, ideal behavior/life scenario instructions, and tape-recorded relaxation practices before each A-T session. The following show initial A-T training sessions and subsequent training sessions, indicating the crossover event occurring in single-channel and two-channel training approaches.

Initial A-T neurofeedback training session.The initial increase in alpha amplitude is followed by a decrease in alpha amplitude to the point where the theta amplitude is greater than the alpha amplitude resulting in brief crossover events.

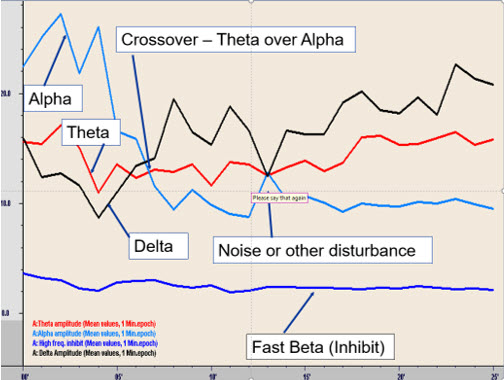

A later session of A-T training initially indicated the increase in alpha as the eyes are closed, followed by a transition to a decreased alpha with increased theta amplitude, resulting in a prolonged crossover experience.

In an early training session with the client using two channels at parietal locations P3 and P4, there are some crossover events. The primary finding is a significant decrease in the 13-36 Hz activity that indicates a marked decrease in the initial overactivity of the central nervous system.

This graphic represents a later session with the same client showing prolonged crossover and an increase in phase synchrony between the two parietal locations in the 5.5-8.5 Hz frequency band used in this case.